Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

Many factors control the distribution of moisture in mountains. The trend of pre-

cipitation increasing with altitude is well known, although, above a certain maximum

altitude, precipitation may again decrease. This is especially evident in the tropics.

While the intermediate slopes of Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya contain luxuriant vegeta-

tion, the summit areas are desert-like (Hedberg 1996). Strong contrasts in precipitation

between the leeward and windward sides of mountains and differences in the effects of

solar intensity and the distribution of sunlight on slopes produce different rates of heat-

ing and evaporation. Snow remains in place longer than rain, but is highly susceptible

to further transport by wind. Exposed ridges and slopes are often snow-free and dry,

while lee slopes become loaded with snow and retain snow patches that provide melt-

water well into the summer. The distribution and redistribution of snow affect soil chem-

istry (Liptzin and Seastedt 2009) and also influence the location of permafrost patches

in midlatitude mountains (Ives 1973; Ives and Barry 1994).

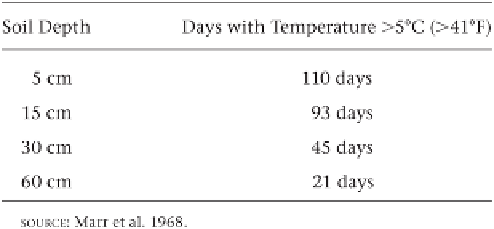

TABLE 6.1

Numbers of Days with Soil Temperatures above 5°C on Niwot Ridge, Colorado

The lack of moisture in arid landscapes reduces biological activity, organic material,

and decomposition rates. Where water is not available to promote chemical weathering,

physical weathering processes become relatively more important. Excess moisture, on

the other hand, results in waterlogging, poor aeration, and increased soil acidity. The

most productive soils develop in intermediate, well-watered, but adequately drained

sites; but mountain sites, such as exposed slopes and ridges or poorly drained meadows

and bogs, often have a scarcity or an excess of moisture.

Wind achieves major importance as a climatic factor by causing evaporative stress

on vegetated and bare surfaces, either directly or indirectly through the redistribution

of snow. Wind also erodes and removes fine material from exposed surfaces, especially

where frost action has left the soil susceptible to transport. Wind erosion is frequently

observed at unvegetated sites around glacial and stream deposits, where ample fine ma-

terial is available.

The corollary to erosion is deposition. Although some fine particles are blown away

from the mountains, some are deposited locally and contribute to soil development.

Volcanic ash is an important wind-borne source of soil material. In addition, very fine

particles from nearby lowlands may be transported by wind into the mountains. The

local-scale distribution of wind-deposited material is similar to that of snow, and the

Search WWH ::

Custom Search