Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

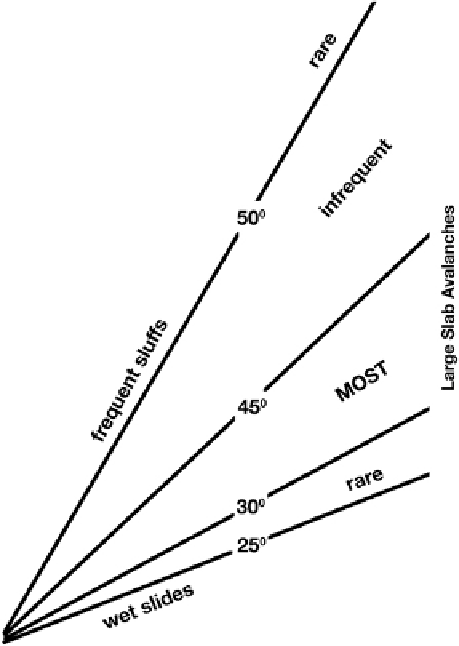

FIGURE 4.22

Characteristic slope angles for snow avalanches. (L. R. Dexter and K. Birkeland.)

Many other terrain features favor or inhibit avalanches. For example, a convex slope

will be slightly more prone to avalanches than a concave slope, as the outward bend of

a convex slope puts tensional stress on its snowcover, while a concavity of slope slightly

strengthens the snow's cohesion through compression. More important than the slope

shape is its orientation with respect to both the wind and the sun. Leeward slopes are

typically more dangerous, since the wind can quickly load large quantities of snow onto

the slope. They are also often overhung by

cornices,

which can fall on the slope and

act as triggers (Figs. 4.19, 4.23). Exposure to the sun greatly influences the behavi-

or of snow. North-facing slopes receive little sun during the winter (in the northern

hemisphere). This typically results in cold conditions where instabilities may persist for

longer periods. On south-facing slopes (in the northern hemisphere), the sun strikes

the surfaces at a higher angle, causing kinetic and/or melt-refreeze metamorphism.

South-facing slopes can be sites of instability because of near-surface faceting (Birke-

land 1998) and wet-snow avalanches (McClung and Schaerer 2006).

Other important terrain variables include surface roughness and groundcover. A

slope strewn with large boulders is not as susceptible to avalanching as a smooth sur-

face, at least until the snow covers the boulders. On the other hand, a smooth, grassy

slope provides no major surface inequalities to be filled by the snow and offers little

Search WWH ::

Custom Search