Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

no mountains. The resulting snowline, although only theoretical, is useful for purposes

of generalization. This is particularly true when investigating temperatures during the

glacial age. For example, if a glacier exists today at 2,000 m (6,600 ft) that at one time

extended to 1,000 m (3,300 ft), the difference in elevation can be converted to temperat-

ure (through use of the vertical lapse rate) to get an approximate idea of the temperat-

ure necessary to produce the lower snowline. There is some evidence that temperatures

during the Pleistocene glacials were about 4-7°C (7-13°F) lower than they are today

(Wright 1961; Flint 1971: 72; Andrews 1975: 5; Porter 2001).

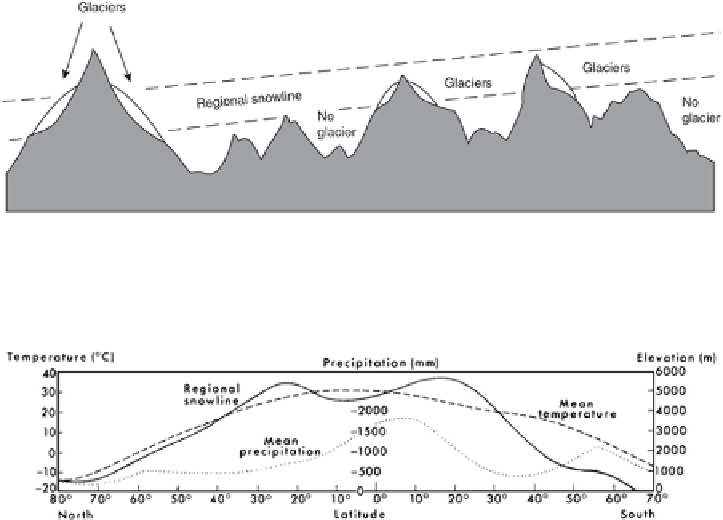

FIGURE 4.11

Method of approximating the regional snowline. The regional snowline occupies the

zone lying between the highest peaks not supporting glaciers and the lowest peaks that do sup-

port glaciers. (After Flint 1971: 64 and Østrem 1974: 230.)

FIGURE 4.12

Generalized altitude of snowline on a north-south basis. The reason for a slightly de-

pressed snowline elevation in the tropics is the increased precipitation and cloudiness in these lat-

itudes. Mean temperature and mean precipitation are also illustrated. (After Charlesworth 1957:

9.)

A more useful approach is to establish a zone or band about 200 m (660 ft) thick

to represent the

regional snowline,

or the

glaciation level

as it is known, since it rep-

resents the minimum elevation in any given region where a glacier may form (Østr-

em 1964a, 1974; Porter 1977, 2001). The location of this zone is based on the differ-

ence in elevation between the lowest peak in an area bearing small glaciers and the

highest peak in the same area without a glacier (but with slopes gentle enough to retain

snow). For example, if one mountain is 2,000 m (6,600 ft) high but has no glacier even

though its slopes are gentle enough to accommodate one, and another mountain 2,200

m (7,300 ft) high does have a glacier, the local glaciation level and the regional snowline

lie between these two elevations (Østrem 1974: 230-233; Fig. 4.11).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search