Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

and cold fronts lift moist, warm air over cooler, denser air. This takes place primarily in

the middle latitudes in association with the polar front (Fig. 3.2). Although both of these

processes can operate without the presence of mountains, their effectiveness is greatly

increased on the windward sides of mountains and decreases on the leeward sides.

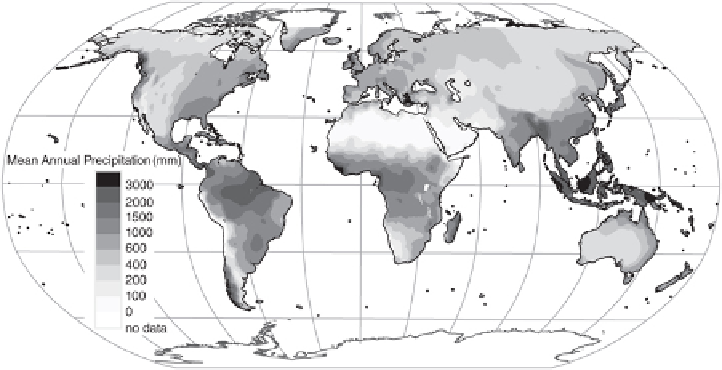

FIGURE 3.17

Annual average precipitation. (From several sources.)

One has only to compare the distribution of world precipitation with the location of

mountains to see the profound influence of those mountains (Fig. 3.17). Almost every

area of heavy rainfall is associated with mountains. In general, any area outside the

tropics receiving more than 2,500 mm (100 in.), and any area within the tropics re-

ceiving more than 5,000 mm (200 in.), is experiencing a climate affected by moun-

tains. In addition to the examples of Cherrapunji, Assam, Mount Waialeale, Hawai'i, and

the Olympic Mountains, given earlier, many others could be added, including Mount

Cameroon, West Africa, the Ghats along the west coast of India, the Scottish Highlands,

the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, and the Southern Alps of New Zealand. The reverse is

also true, for in the lee of each of these ranges is a rainshadow in which precipitation de-

creases drastically (Sklenář and Lægaard 2003; Smith et al. 2009). The western Ghats

receive over 5,000 mm (200 in.), but immediately to their lee, on the Deccan Plateau,

the average precipitation is only 380 mm (15 in.). The windward slopes of the Scottish

Highlands receive over 4,300 mm (170 in.), but the lowlands around the Moray Firth

receive 600 mm (24 in.). The Blue Mountains of northeast Jamaica face the trade winds

and receive over 5,600 mm (220 in.), while Kingston, 56 km (35 mi) to the leeward, re-

ceives only 780 mm (31 in.). Mountains, therefore, not only cause increased precipita-

tion, but also have the reciprocal effect of decreasing precipitation.

Despite these useful generalities, many local and regional variations occur within

mountains. The complex local topography creates funneling effects that can increase at-

mospheric moisture content and precipitation, even downwind from the funnel (Sinclair

et al. 1997). High peaks or ridges can create “mini-rainshadow” zones, even in the cen-

ter of a range (Garreaud 1999). Significant quantities of precipitation can fall on the lee

Search WWH ::

Custom Search