Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

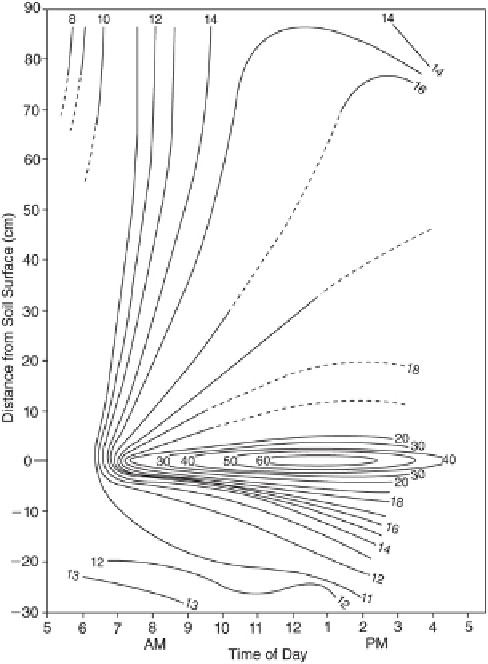

FIGURE 3.13

Vertical profile of soil and air temperatures (°C) under clear skies on a well-drained

alpine tundra surface at 3,580 m (11,740 ft) in the White Mountains of California. Note the tre-

mendous gradient occurring immediately above and below the soil surface. The slightly higher

temperatures at a depth of 25-30 cm (10-12 in.) are a result of the previous day's heating and are

out of phase with present surface conditions. (After Terjung et al. 1969: 256.)

Such a temperature regime stands in great contrast to that of tropical mountains.

Figure 3.14b shows the temperature characteristics of Quito, Ecuador, on the equator at

an elevation of 2,850 m (9,350 ft). The isotherms on the graph are oriented vertically, in-

dicating very little change between winter and summer, but a marked contrast between

day and night. The average annual range is less than 1°C (1.8°F), while the average

daily range is approximately 11°C (19.8°F). This beautifully demonstrates the saying,

“Night is the winter of the tropics.” This is particularly true if the station is high enough

for freezing to occur.

The lower limit of frost is determined principally by latitude, mountain mass, contin-

entality, and the local topographic situation. In the equatorial Andes, it is at about 3,000

m (10,000 ft). The elevation of this limit decreases with latitude; the point where frost

begins to occur in the lowlands is normally taken as being the outer limit of the tropics.

In North America, the frost line runs through the middle of Baja California and eastward

Search WWH ::

Custom Search