Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

mountains is largely a response to solar radiation. The free air, however, essentially does

not respond to the heating effects of the sun, particularly at higher altitudes. A moun-

tain becomes heated at the surface but there is a rapid temperature gradient in the

surrounding air. Consequently, only a thin boundary layer or thermal shell surrounds

the mountain, its exact thickness depending on a variety of factors (e.g., solar intensity,

mountain mass, humidity, wind velocity, surface conditions, and topographic setting).

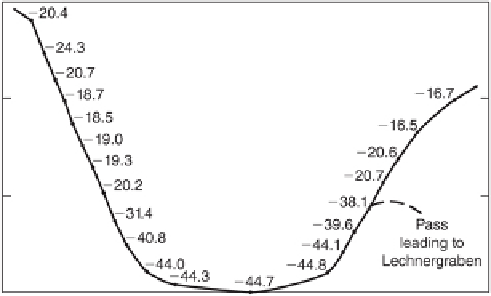

FIGURE 3.11

Cross section of an enclosed basin, Gstettneralm, in the Austrian Alps, showing a tem-

perature inversion in early spring. Elevation of valley bottom is 1,270 m (4,165 ft). Note increase

in temperature (°C) with elevation above valley floor, especially the rapid rise directly above the

pass. This results from the colder air flowing into a lower valley at this point. (After Schmidt 1934:

347.)

FIGURE 3.12

Diurnal temperature range at different elevations on Mount Fuji, Japan. The difference

between high and low altitudes is much more exaggerated in winter (left) than in summer (right).

(After Yoshino 1975: 193.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search