Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

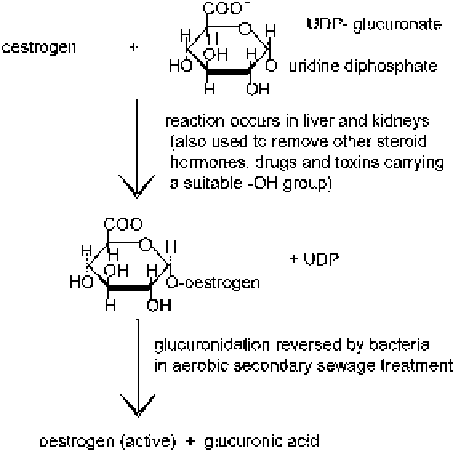

Figure3.1

Glucuronidation

including minnows, trout and flounders. The source of environmental oestrogens

is not confined to outfall from sewage treatment plants, however, the fate of

endocrine disrupters, examples of which are given in Figure 3.2, in sewage treat-

ment plants is the subject of much research (Byrns, 2001). Many other chemicals,

including PAHs, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), alkyl phenols and some

detergents may also mimic the activity of oestrogen. There is general concern

as to the ability of some organisms to accumulate these endocrine disrupters in

addition to the alarm being raised as to the accumulative effects on humans of

oestrogen like activity from a number of xenobiotic sources.

To date there is no absolute evidence of risk to human health but the Environ-

mental Agency and Water UK are recommending the monitoring of environmen-

tal oestrogens in sewage treatment outfall. Assays are being developed further to

make these assessments (Gutendorf and Westendorf, 2001) and to predict poten-

tial endocrine disrupter activity of suspected compounds (Takeyoshi

et al

., 2002).

Oestrogen and progesterone are both heat labile. In addition, oestrogen appears

to be susceptible to treatment with ultra violet light, the effects of which are aug-

mented by titanium dioxide (Coleman

et al

., 2004). The oestrogen is degraded

completely to carbon dioxide and water thus presenting a plausible method for

water polishing prior to consumption.

Another method for the removal of oestrogens from water, in this case

involving

Aspergillus

, has also been proposed (Ridgeway and Wiseman, 1998).

Sulphation of the molecule by isolated mammalian enzymes, as a means of

hormone inactivation is also being investigated (Suiko

et al

., 2000). Taken

overall, it seems unlikely that elevated levels of oestrogen in the waterways

Search WWH ::

Custom Search