Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

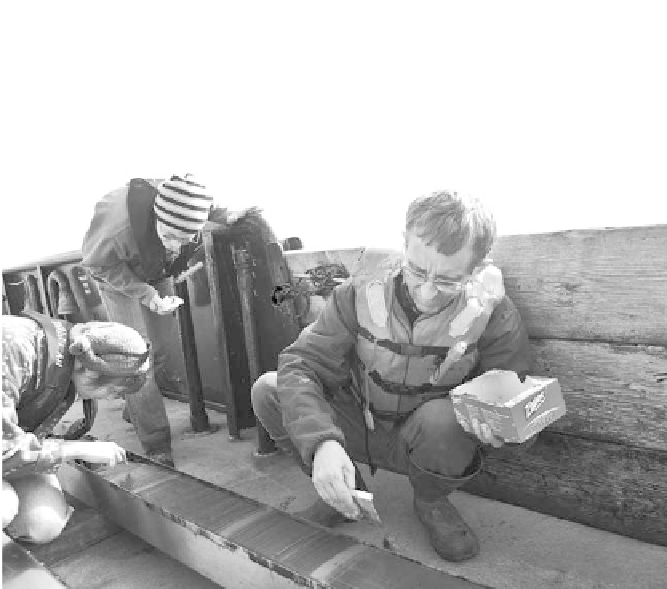

f igu r e 14 . Arndt Schimmelmann and colleagues examining varved sediments cored

from beneath the Santa Barbara Basin along the Southern California coast. (Photo courtesy

of Arndt Schimmelmann, University of Indiana.)

of tree rings, these alternating sedimentary layers can be used to re-create a

timeline by counting from the top of the core downward, with each pair of

light and dark sediment layers representing one year (see i gure 14).

Fossils of phytoplankton and other microscopic marine organisms contain

information about changing water temperatures, coastal upwelling, nutrient

levels, and ocean circulation. Pollen blown into coastal waters and preserved

in accumulating sediments provides information about past vegetation

from nearby coastal regions, and the composition and amount of sediments

carried by rivers contain clues about precipitation and runof , including the

relative size of l oods.

On land, sediments deposited in freshwater environments can also be

great preservers of paleoclimate information. Lakes, ponds, swamps, and

marshes—all damp, mostly low-oxygen environments—are ot en character-

ized by slow decomposition processes that allow organic matter to be pre-

served for a long time. In these sediments, the pollen, charcoal fragments,

fossils, organic material, and detrital material, including their chemical and

isotopic compositions, are all used in paleoclimate research. As with the

coastal ocean, lake sediments are obtained by coring the bottom sediments

beneath the water (see i gure 15).