Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

What we do....

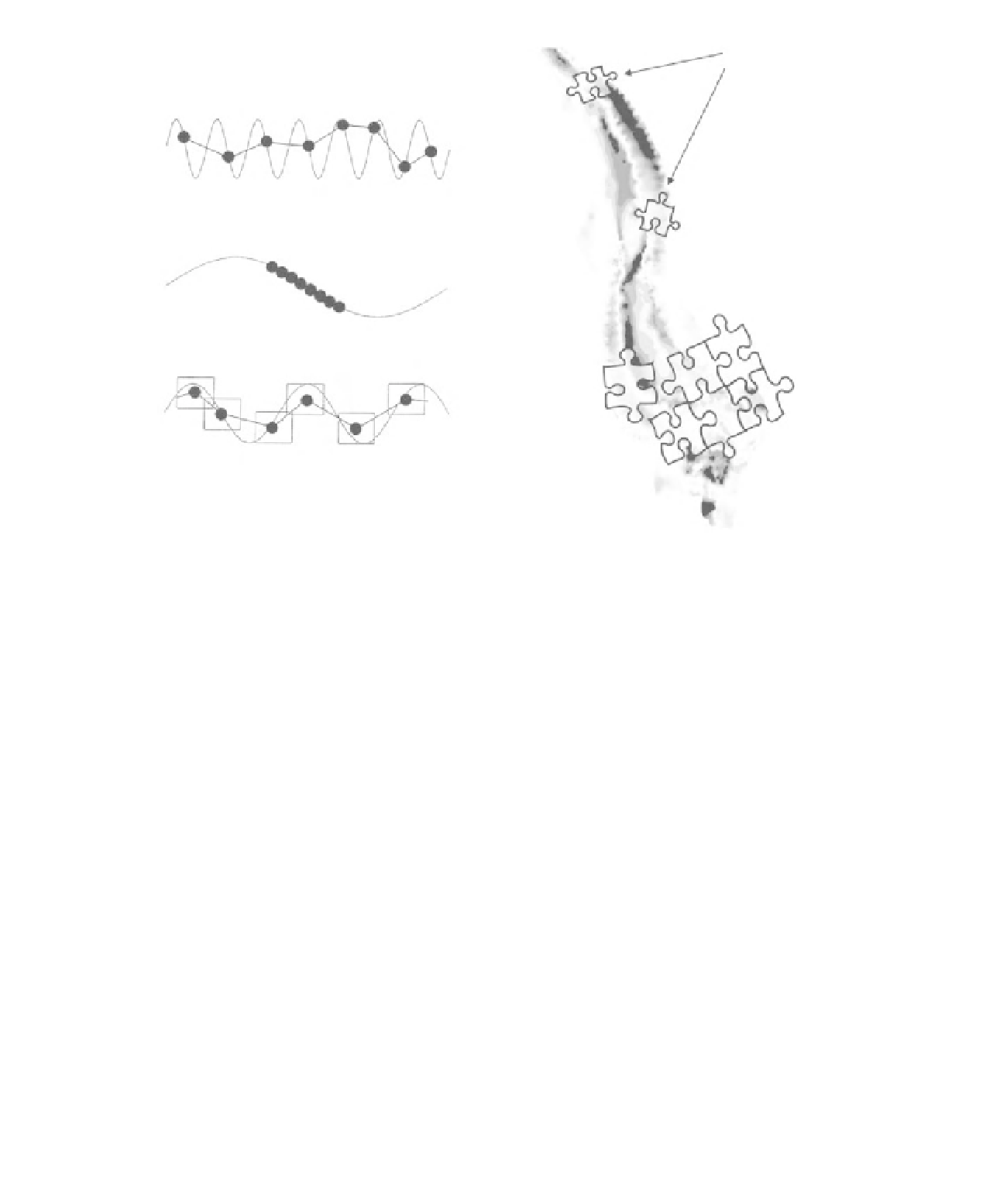

Traditional, static/taxonomic,

unit-based constrained

sampling (e.g. riffle-pool for

BMWP).

Resolution (spacing) larger than the process scale causing aliasing in

the data. The result is environmental noise.

Extent of survey smaller than the process scale. The result can be an

impression of trend, where in reality there is none.

Spatial or time support too large compared with the process scale. The

result is excessive smoothing of patterns.

What we need....

Predictive and

adaptive

monitoring

(edges and patches,

persistence, resilience,

robustness).

Figure 31.3

How rivers are traditionally sampled, problems with resolution of sampling in time series datasets (after

Bl oschl, 1996), and what is really needed. Predictive flexible and adaptive monitoring focusing on edges and patches

will help to avoid some of the data issues shown (after Bloschl, 1996).

(Dollar, 2004). A major contribution of fluvial

geomorphology is the ability to assess whether

channels can restore themselves if left alone, or

encouraged - through assisted natural recovery - to

achieve a potentially much cheaper way for river

restoration compared with costly engineered

solutions (Brookes and Shields, 1996; Sear

et al

., 2009). Nevertheless, there are still dangers

in drawing conclusions from incomplete or

inappropriate information. For example, rapid

assessment tools developed to characterize river

channels are too generalist at the point of

their application and, despite being based on

'expert knowledge', are often flawed owing to

inadequate local knowledge of river behaviour.

Recent advances of in-channel three dimensional

modelling

approach. For example, in seeking to evaluate site-

specific rather than generalized Habitat Suitability

Indices, the European Aquatic Monitoring Network

compares habitat suitability criteria developed for

individual river reaches, specifying only one flow-

dependent biotope type per reach; the consequence

is that the data are combined from different

sites at different flows and different times of

year (EAMN, 2004). In contrast, others have

used newly available methods such as terrestrial

laser scanning to refine scales of investigation

significantly (Heritage

et al

., 2009; Milan

et al

.,

2010). Both approaches are justified, depending on

the purpose of study; generalized information is

useful for strategic management decisions, while

more

sophisticated

investigation

can

focus

on

offer

a

useful

way

of

filling

these

the

relevant

scale

for

specific

biota

by

using

knowledge gaps (Clifford

et al

., 2006, 2010).

A range of habitat quantification methods has

been developed but these vary widely in their

features

such

as

water

surface

roughness

as

indicators

of

micro-scale

hydraulic

variability.

Effective

characterization

of

hydromorphology