Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

At the same time, Deer Creek is a critical

habitat for the remnants of spring-run chinook

salmon (

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

), a species listed

as threatened under the US Endangered Species

Act. As the Sacramento River and its major

tributaries were dammed in the 20th century, Deer

Creek (along with other small tributaries, Mill and

Butte Creeks) assumed greater importance as a fish

habitat. The salmon traverse the lower, alluvial

reach en route to remote canyons cut into volcanic

rocks that offer them suitable spawning and rearing

habitat. Autumn-run chinook use the alluvial

reach for spawning, and spring-run, winter-run,

and other salmonids, mostly from other drainages,

use the alluvial reach for (non-natal) rearing.

However, habitat quality is limited by lack of

riparian vegetation and shade, the channel form

is very simple, and the gravel sizes (D

50

from

55-190 mm) are larger than ideal for chinook

salmon spawning (Kondolf and Wolman, 1993).

The channel lacks complex features that provide

good habitat, such as tight bends and secondary

circulations, undercut banks, scour pools, woody

debris jams, and a well-developed pool-riffle

sequence. In response to these problems, salmon

restoration programmes in the 1990s proposed

planting vegetation along the low-flow channel

banks and mechanically constructing spawning

riffles by adding smaller-sized gravels to the creek

(CDFG, 1993; USFWS, 1995; CALFED, 1997).

However, a geomorphic analysis concluded that

the underlying cause of the habitat degradation

was the flood control project (DCWC, 1998).

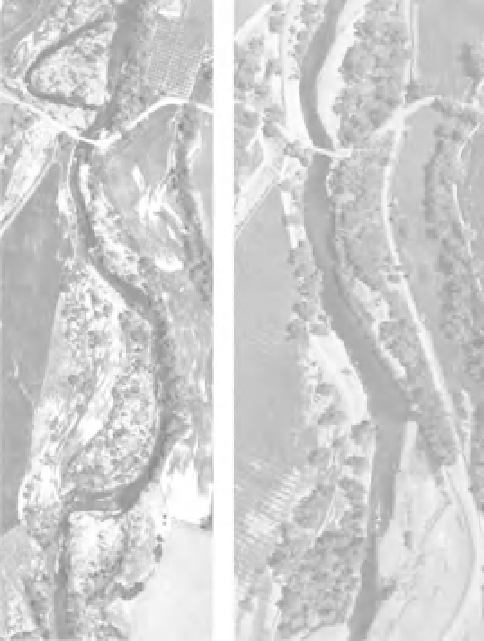

Aerial photographs from 1938 showed that before

the flood control project the channel was highly

complex, with frequent pool-riffle alternations,

meander bends, and gravel bars, with trees

overhanging the channel, undercut banks and

log jams (Figure 18.10a). Aerial photographs

taken after the flood control project showed a

marked simplification of the channel and thus

loss of habitat (Figure 18.10b). Moreover, channel

maintenance requires clearing accumulated gravel

bars, and levees constrain high flows within

the low-flow channel (concentrating flow and

increasing shear stress on the channel bed more

than when floods overflowed from the channel)

(a)

(b)

Figure 18.10

Details from aerial photographs of alluvial

Lower Deer Creek (a) in 1938, and (b) 1997, showing

the transformation of Deer Creek from a multi-threaded,

complex channel to a simplified, wider main channel

with higher shear stress in floods. Also visible in the

1997 photo detail is the levee breach along the left

(south) bank. Flow is from top to bottom, length of river

shown is about 1100 m.

(DCWC, 1998). Thus, if, as had been recommended

by the salmon restoration programme, riparian

vegetation were to be planted and spawning riffles

constructed, they would probably wash out in

the high shear stresses of the constrained levee

system. With the process altered by the levees, such

constructed forms would be unlikely to persist.

Thus, the habitat problems previously identified

along Deer Creek (lack of shading, simplified

channel form and too-coarse spawning gravels)

were all symptoms of an underlying cause:

the effects of a flood control project built five

decades before. Rather than spend restoration

funds on treating the symptoms (planting trees