Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

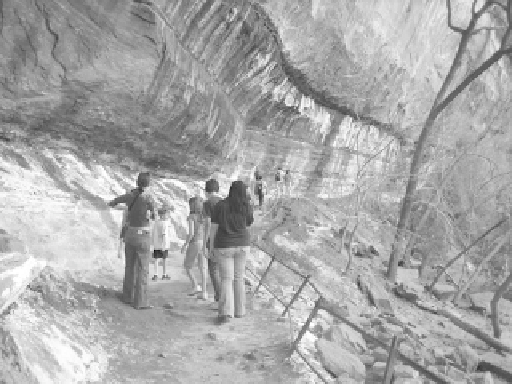

Figure 5.5

This trail is experiencing signifi cant wear and tear, and its railing is

beginning to fail

cultural past requires a great deal of care to ensure that it does not diminish

through tourism. The effects of trail use on tangible culture are manifold.

One impact is the physical damage that thousands of feet, tires or hooves

inflict on cultural trails (Figure 5.5). Jones (2001) examined the physical

impacts of mass tourism on the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu in Peru and

concluded that as the 33 km pathway leading to the citadel has grown in

popularity in recent decades, its carrying capacity has been exceeded, result-

ing in visible damage to the historic track and its pavestones. Similar condi-

tions can be seen on several sections of original Roman roads in Europe.

Countryside rambling also raises additional concerns for the cultural

heritage of places. Overuse of footpaths and tramping through the country-

side can damage cultural landscapes and archaeological relics (Hornby &

Sheate, 2001). As well, historic buildings and archaeological sites near path-

ways are regularly looted for artifacts and other collectibles owing to a lack

of monitoring and oversight. Underwater marine trails are notorious for trea-

sure hunters and vandals (Alves, 2008; Leshikar-Denton & Scott-Ireton,

2007; Smith, 2007). Scott-Ireton (2007) noted the damage done to a ship-

wreck in Lake George, New York, when divers attempted to remove two

cannon port lids. These kinds of situations are not uncommon under water

where it is difficult to monitor users' behavior.

Despite the ecological impact arising from trail use, it also important to

gauge if there is any difference in the reaction to physical impacts by tourists

and residents. Much of the research has focused on national parks on visitor

(tourists versus residents) perceptions of trail conditions (e.g. Noe

et al.

, 1997)

or impacts at campsites (e.g. Shelby

et al.

, 1998; van Winkle & MacKay,

Search WWH ::

Custom Search