Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

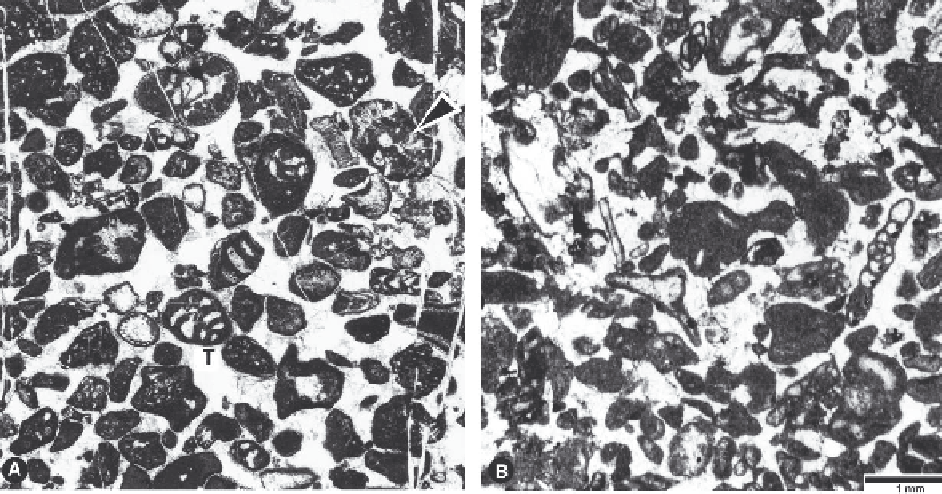

Fig. 14.28.

SMF Types assist in recognizing facies belts independently of the age of the rocks.

Note the amazing similarity in

grain composition and depositional texture of the two samples from Jurassic and Cretaceous limestones. Both samples

represent SMF 17, characteristic for sediments formed in platform interior environments when water depth has remained

relatively constant (late highstand phase). The similarity includes not only the grainstone texture and the dominance of

aggregate grains but also the occurrence of benthic foraminifera and algae, indicating very shallow warm-water sedimentation.

A:

Thick-bedded limestone within a subtidal shallowing-upward sequence.

Foraminifera are textulariids and

Trocholina

(T).

Green algae are represented by fragments of

Clypeina

(arrow).

Late Jurassic: Sulzfluh, Graubünden, Switzerland.

B:

Thin-bedded lagoonal limestone at the base of a mixed siliciclastic-carbonate sequence. Miliolid foraminifera are

Cyclogyra

(right) and

Quinqueloculina

(center top). Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian): Monastery St.Anthony, Eastern Desert, Egypt.

Scale valid for both pictures. After Kuss (1986).

Occurrence:

Removal of fine-grained sediment by

strong winnowing occurs in high-energy near-coast en-

vironments (FZ 7), but also through bottom currents,

e.g. in deep shelf and basinal environments (FZ 2 and

FZ 1).

SMF 15 characterized by ooids, SMF 16 defined by

accumulations of peloids, and SMF 17 typifying car-

bonates rich in aggregate grains are frequent constitu-

ents of shallow platform carbonates. SMF 15 and SMF

16 are also common in inner- and mid-ramps in con-

trast to SMF 17 that appears to be very rare in ramp

carbonates, but is an excellent indicator for platform

interior environments (Fig. 14.28). These three SMF

Types are easy to recognize if the diagnostic grains

dominate quantitatively. Many samples, however, con-

tain mixtures of aggregate grains and peloids, or ag-

gregate grains, peloids and skeletal grains. The assign-

ment of these samples to one of the SMF Types may be

somewhat tricky.

SMF 18 characterizing accumulations of foramin-

iferal shells or calcareous green algae is well-defined

but unites accumulations having different origins. The

miliolid foraminiferal sand of Pl. 122/1 is an autoch-

thonous sediment as indicated by the good preserva-

tion of the foraminiferal tests and their association with

aggregate grains. Pl. 122/2 demonstrates the formation

of a coarse algal sand through the disintegration of dasy-

clad thalli. Disintegration was stronger for the gymno-

codiacean algae (Pl. 122/3) that fell apart into smaller

particles than the dasyclad algae. Both samples show

how algae contribute to in-place sediment production,

but the dasyclad living in high-energy areas, where most

of the mud has been winnowed, produced skeletal sand

recorded by a grainstone fabric, whereas the gymno-

codiacean algae living in a low-energy environment pro-

duced lime mud. Contrasting these examples, the Cre-

taceous foraminiferal grainstone depicted in Fig. 14.23

was formed by a short storm event that may have oc-

curred in different parts of the platforms and ramps. A

closer look at the taxonomic composition of the fora-

miniferal fauna may tell you in which ecological zones

the tests have been reworked (see Fig. 14.7).

The joint characteristic of SMF 19, SMF 20 and

sometimes also of SMF 21 is a fine biogenic lamina-

tion whose origin is related to trapping and binding ac-

tivities of microbes and algae, and to the precipitation