Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

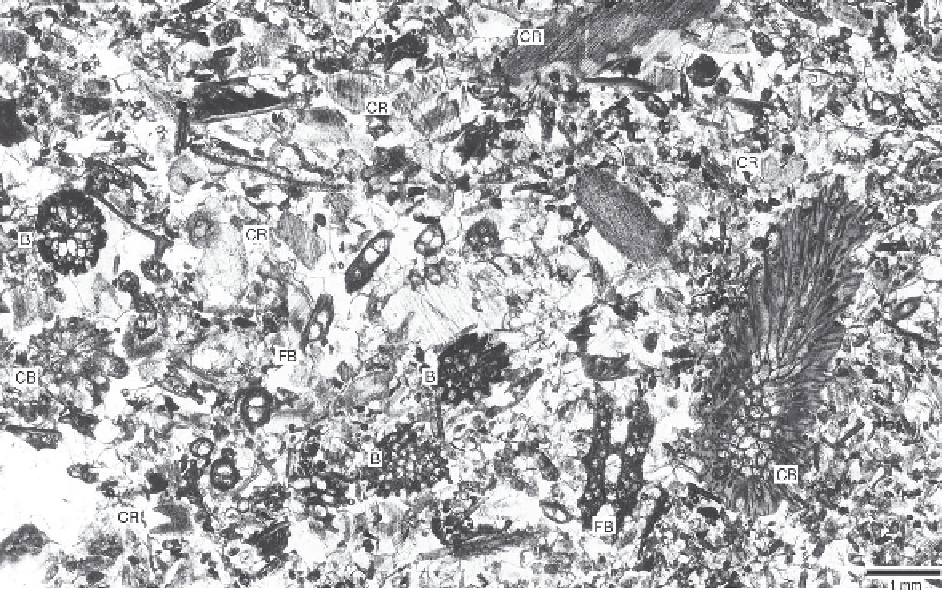

Fig. 12.9.

Recognition of substrate stability by benthic assemblages.

The sample exhibits a skeletal grainstone with bryozoans

(B) and crinoids (CR). This assemblage is typical for many Mississippian open-marine shelf limestones. The grain-supported

texture indicates deposition of skeletal sand forming a firmground substrate. Most grains are not significantly abraded. The

skeletal grains are of different sizes. Bryozoans represent two morphotypes (fenestrate forms - FB, and ramose cryptostomid

forms - CB). Most cryptostomid bryozoans are well preserved, indicating only limited reworking. These bryozoans are

regarded as autochthonous components of the assemblage. Fenestrate bryozoans grew as loose sheets over the substrate. The

preservation of crinoids as isolated elements showing no signs of strong reworking and the dominance of sessile organisms

unable to tolerate shifting substrates suggest stable substrate conditions. Similar patterns were described by Feldman et al.

(1993). Early Carboniferous: Calgary, Canadian Rocky Mountains.

Plate 103 Soft Bottoms and Hard Substrates

The sea bottom differs in consistency and stability of the sediment. Non-cemented carbonate muds and sands

form soft bottoms, lithified carbonate sediments form hard bottoms. The state of consistency and stability prior

to lithification can be inferred from paleontological and textural criteria.

1

Soft bottoms and hard substrates

demonstrated by a poorly sorted skeletal floatstone. The fine-grained micritic matrix is

a strongly burrowed bioclastic wackestone with shell debris. Larger fossils are radiolitid rudist bivalves (R), corals (C)

and siliceous sponges (S). Rudists and corals are encrusted by coralline red algae (A). Criteria indicating substrate condi-

tions are burrows and borings. Burrows (B) within the wackestone matrix are common but hard to recognize at a first

view. Look at the typical, here only faintly visible, subrounded outline (white arrows), the slightly darker color and the

close setting of the burrows. These criteria characterize a soft silty looseground substrate (Goldring 1995) with slight

stabilization enabling the settlement of serpulid worms (SER). Corals and rudist shells form local hard substrates as

indicated by borings and biogenic encrustation. The borings (BO) in the rudists have affected both the inner aragonitic

and the outer calcitic shell layers. The borings marked by black arrows tell a different story. They transect the sedimentary

fabric and are filled with gray crystal silt. These criteria show that the borers did not attack individual fossils but the whole

rock and that this attack took place in a meteorically influenced post-lithification stage. The sample comes from a small

reef mound consisting of floatstones and rudstones, and local coral and rudist boundstones. Late Cretaceous: Haidach

near Brandenberg, Tyrol, Austria.

Courtesy of D. Sanders (Innsbruck).