Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

float as long as the skeletal elements are filled with

organic tissue, was discussed by Ruhrmann (1971b).

Submarine fissures and neptunian dikes formed after

drowning of carbonate platforms can act as traps for

crinoid accumulations (Pl. 24/4, Pl. 139/6). Deposition

on seamounts is believed to have been controlled by

submarine currents (Jenkyns 1971).

The

differentiation of depositional environments of

crinoid limestones

requires answers to the following

questions:

•

Which elements of the crinoids have been preferen-

tially deposited (stems, columnals, plates, brachials

etc.)?

•

How well preserved are the elements (e.g. totally or

partly disarticulated, long crinoid stems or even

crinoid crowns)?

•

Are the crinoid elements broken, worn, abraded or

conspicuously altered (Pl. 95/3, 4)?

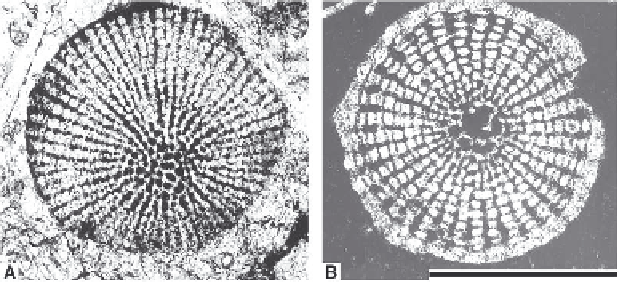

Fig. 10.56.

Saccocoma

limestone.

A

: This microfacies is char-

acterized by numerous antler-shaped calcitic structures float-

ing in a fine-grained matrix of pelagic micrite. Late Jurassic

(Kimmeridgian): Central Apennines, Italy.

B

: Cross section

of a

Saccocoma

arm element (brachialia). Late Jurassic:

Thurburbo majus, northern Tunisia. Scale is 500

m.

•

Do crinoid stems show signs of current orientation?

•

Are the elements bored or encrusted (Pl. 52/6, 7)?

•

How abundant are the crinoids with regard to the

rock volume?

•

Are the crinoid elements grain- or mud-supported?

and occur with

Saccocoma

Agassiz in great abundance

in Tethyan Jurassic open-marine limestones as well as

in epicontinental shelf carbonates (Fig. 10.56).

•

What about the sorting of crinoids and other grains?

•

Do crinoids contribute to specific depositional fab-

rics (e.g. gradation, lamination)?

•

What other skeletal and non-skeletal grains are as-

sociated with the crinoids (Pl. 95/1)?

Triassic roveocrinoids

(Pl. 96/1) occur in wide dis-

tribution in the Tethys within a specific time interval

comprising the Late Ladinian and the Early Carnian

(Kristan-Tollmann 1970).

Other important questions in the context of the ge-

netic interpretation of crinoid limestones refer to field

criteria (geometry, sedimentary structures), lateral and

vertical extension of the crinoid limestones, and inter-

bedding with other facies types.

The first record of

Saccocoma

is from late Middle

Jurassic, mass occurrences are abundant within the time

interval Kimmeridgian to middle Tithonian. The plank-

tonic life-style of

Saccocoma

was questioned by Manni

et al. (1997) who favored a possible benthic mode of

life. Anatomical and taphonomical criteria as well as

the distributional pattern argue against this interpreta-

tion (Keupp and Matyszkiewicz 1997).

Planktonic crinoids

Elements of non-stalked planktonic crinoids are im-

portant, sometimes rock-forming constituents of pelagic

carbonates. These crinoids are known from the Trias-

sic of the Alpine-Mediterranean region (roveocrinoids)

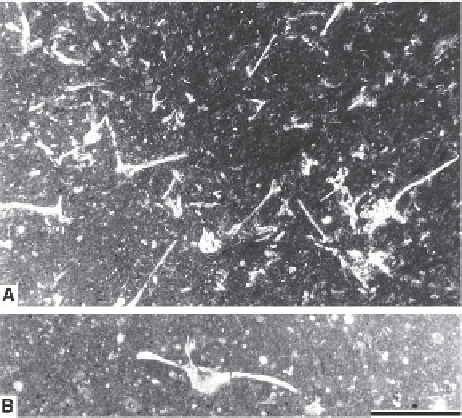

Fig. 10.57.

Echinoid spines with

stereom-filled center.

The pattern cor-

responds to the

Cidaris

type distin-

guished by Hesse (1900).

A

: The reticu-

late structure of the central zone is sur-

rounded by a zone of densely arranged

radial septa. The septa are connected by

rings of interseptal bars.

B

: The gen-

eral structural pattern resembles that of

A but the spine is covered by a distinct

peripheral border. A and B: Early Per-

mian: Forni Avoltri, Carnia, Italy. Scale

is 500

m.