Hardware Reference

In-Depth Information

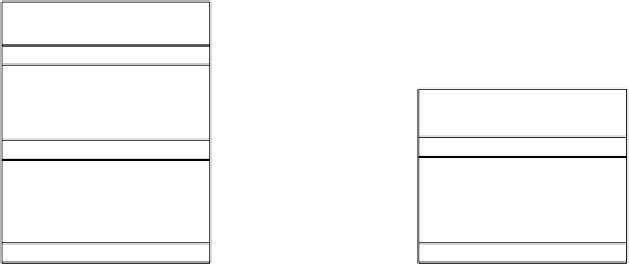

Object module A

Object module B

400

600

CALL B

300

500

CALL C

200

400

MOVE PTOX

300

MOVE QTOX

100

BRANCH TO 200

200

0

100

Object module C

500

BRANCH TO 300

0

400

CALL D

Object module D

300

300

200

MOVE STOX

MOVE RTOX

200

100

100

0

0

BRANCH TO 200

BRANCH TO 200

Figure 7-13.

Each module has its own address space, starting at 0.

300. In fact, all memory reference instructions will fail for the same reason.

Clearly something has to be done.

This problem, called the

relocation problem

, occurs because each object mod-

ule in Fig. 7-13 represents a separate address space. On a machine with a seg-

mented address space, such as the x86, theoretically each object module could

have its own address space by being placed in its own segment. However,

OS/2

was the only operating system for the x86 that supported this concept. All versions

of Windows and

UNIX

support only one linear address space, so all the object

modules must be merged together into a single address space.

Furthermore, the procedure call instructions in Fig. 7-14(a) will not work ei-

ther. At address 400, the programmer had intended to call object module

B

, but be-

cause each procedure is translated by itself, the assembler has no way of knowing

what address to insert into the

CALL B

instruction. The address of object module

B

is not known until linking time. This problem is called the

external reference

problem. Both of these problems can be solved in a simple way by the linker.

The linker merges the separate address spaces of the object modules into a sin-

gle linear address space in the following steps: