Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

48

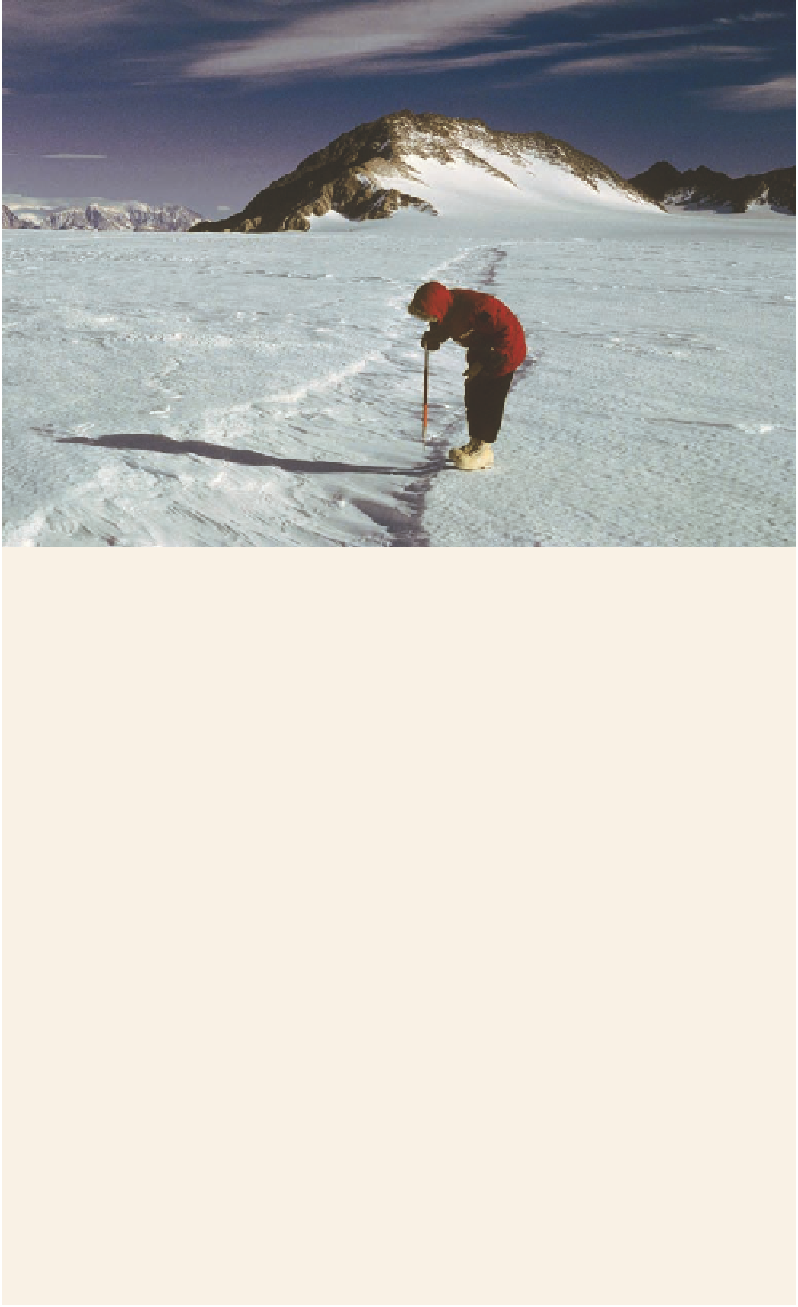

Figure S.3. Probing a

bridged crevasse is the only

way to tell whether it is

safe to cross.

played off to the right into a slightly larger room that pinched to nothing at its

bottom. I wedged my foot across the bottom of the crevasse and looked back

up. I was surrounded by a sculpture illuminated from without. The walls were

translucent gray, strewn through with layers of fine, white bubbles, configured in

blocks that had been broken and then fused into a brittle/ductile, mish-mash of

rehealed ice. I felt as if I were underwater—it was rapture.

I was hooked. Unless there was a particularly good 16mm movie showing at

the camp that night, several of us would hike over to the crevasse field to fool

around in our newfound world within the glacier. When the sun was shining, the

grayness that I had experienced in my first crevasse was transcended by perva-

sive blue, pale and bright near thin spots in an overhanging bridge, dark and rich

deep down in. The blue color is due to absorption of light in the red portion of the

visible spectrum by molecules of water. It is the same in water and in ice. Crevass-

ing is indeed an underwater experience. The deeper down one goes, the purer

becomes the blue (Fig. S.4).

For the second half of the field season, we moved camp to the west side of

Nilsen Plateau. Soon enough we found a promising crevasse about a mile from

camp. It was a big one, marked by subtle sags and cracks in the snow surface,

with its opposing sides separated by more than one hundred feet. How long the

crevasse was we couldn't tell. I poked and chopped at the bridge along one of

the sides and finally got an opening big enough to fit into. The apparent bridge

of the crevasse, rather than spanning a hundred-foot opening, was a solid plug

of ice as far down as I could see. It sat about three feet away from the glacier