Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

47

as

crevasses

. Crevasses open where a glacier accelerates and stretches, and are

oriented perpendicular to the direction of maximum extension (Fig. S.2). Where

glaciers make sharp turns, flow over ridges, or drop from hanging valleys, the

geometry of the crevasses may become chaotic, with huge seracs (ice blocks)

tumbling down icefalls, stationary in human time.

Crevasses are like rattlesnakes—not a problem if you know where they

are, but if you do not see them, they can catch you by surprise. The danger of

a crevasse is that it may be covered by a bridge that conceals a yawning space

below. A crevasse opens in tiny increments, with each brittle fracture separating

the ice by a millimeter or so. As the crack opens, blowing snow sifts down into

it, sealing up the gap and building a bridge that widens at the same pace as the

opening of the crevasse. The bridge is typically thinnest at the edges and droops

in the middle. To detect subtle crevasses, you need to look for faint linear offsets

in the snow, and, if you find one, probe it with an ice axe or a pole to see how thin

and wide it is (Fig. S.3). Then you must decide whether to cross or go around.

I first descended into a crevasse in 1970 about a mile out from our heli-

copter camp on McGregor Glacier. On an overcast day, I was belayed on a rope

from above and climbed down a “crevasse ladder”—a flexible, wired ladder for

crevasse rescue—into a world of deep, soft, and subtle gray. The crevasse was

narrow and not more than six feet wide at the top. The walls reached twenty feet

below to an irregular surface of blocks that had dropped years before from the

underside of the bridge that we had chopped open for our fun. The paired walls

undulated gracefully in symmetrical curves that transcended simple math, then

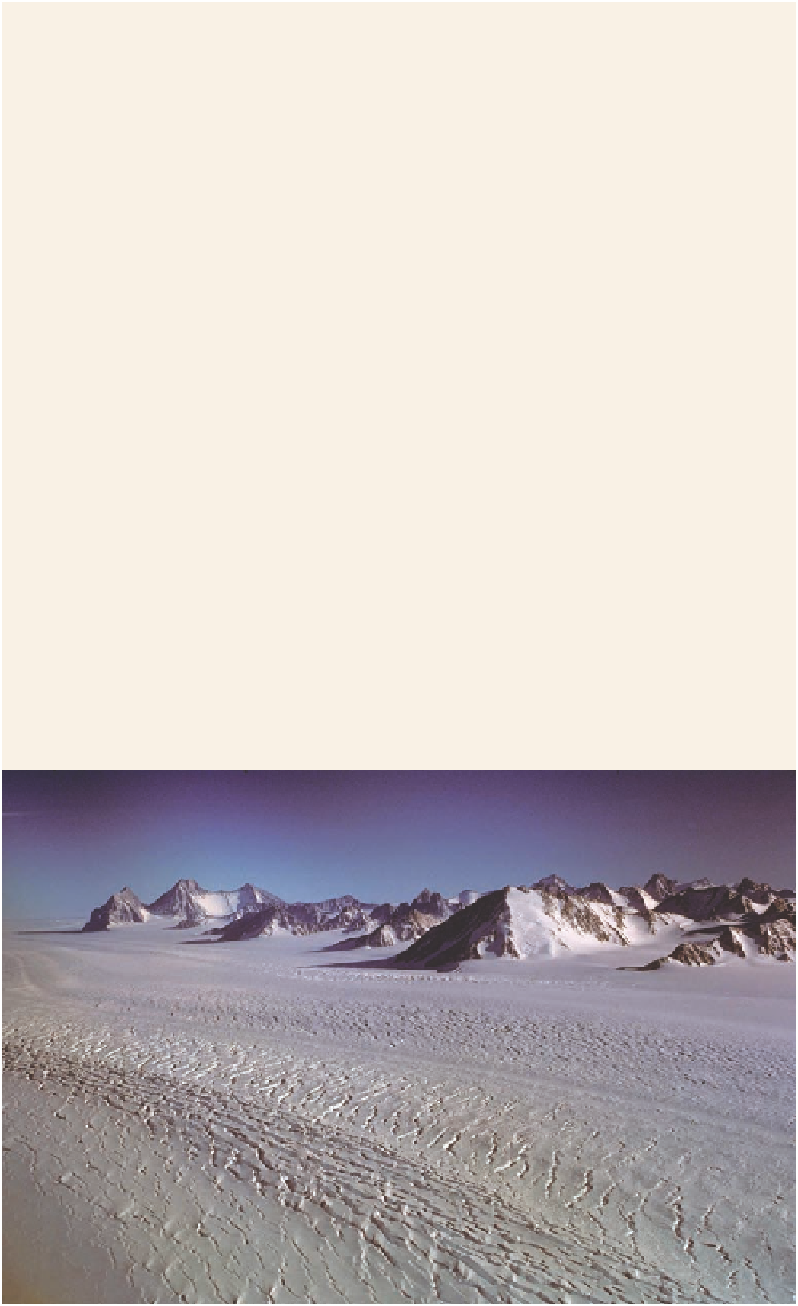

Figure S.2. Crevasses riddle

the surface of Scott Glacier,

one of the major outlet

glaciers that cross the

Transantarctic Mountains

(see Chapter 6).