Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

189

THE WInD

In the static, lifeless landscape of the deep field, the wind is the only animate

force. It is movement and sound, alternately relentless and fickle. When it stops

and the sun beams down from a cloudless sky, you can strip to bare skin and

immediately feel the warmth. But let one puff of breeze disturb the thin layer of

radiant air, and shivers will well up. When the wind picks up, it buffets the parka

and bites at fingertips, ear lobes, and nose. In its full fury the wind has flattened

tents and thrown men from the decks of ships. At these times it is an awesome,

fearsome force.

During the 1980-1981 field season I was camped between Mount Mooney

and the La Gorce Mountains a few miles from our put-in site on Robison Glacier.

For the better part of the two weeks we spent at that camp, frigid, katabatic

winds poured over us from the polar plateau to the southeast. With wind speeds

generally around ten to fifteen knots and temperatures about minus 10° F, our

days mapping the outcrops in the surrounding area were seldom comfortable,

especially along ridgelines where the wind compressed and accelerated.

The La Gorce Mountains at the edge of the polar plateau are a first obstruc-

tion to katabatic winds that originate deep in the interior of the East Antarctic

Ice Sheet. The flat top of these mountains slips smoothly from beneath the ice

sheet and rises to the northwest to a dramatic escarpment that drops steeply

more than three thousand feet and splays into two major ridge systems (see Fig.

6.2). When the katabatic winds meet the southeast or back side of the La Gorce

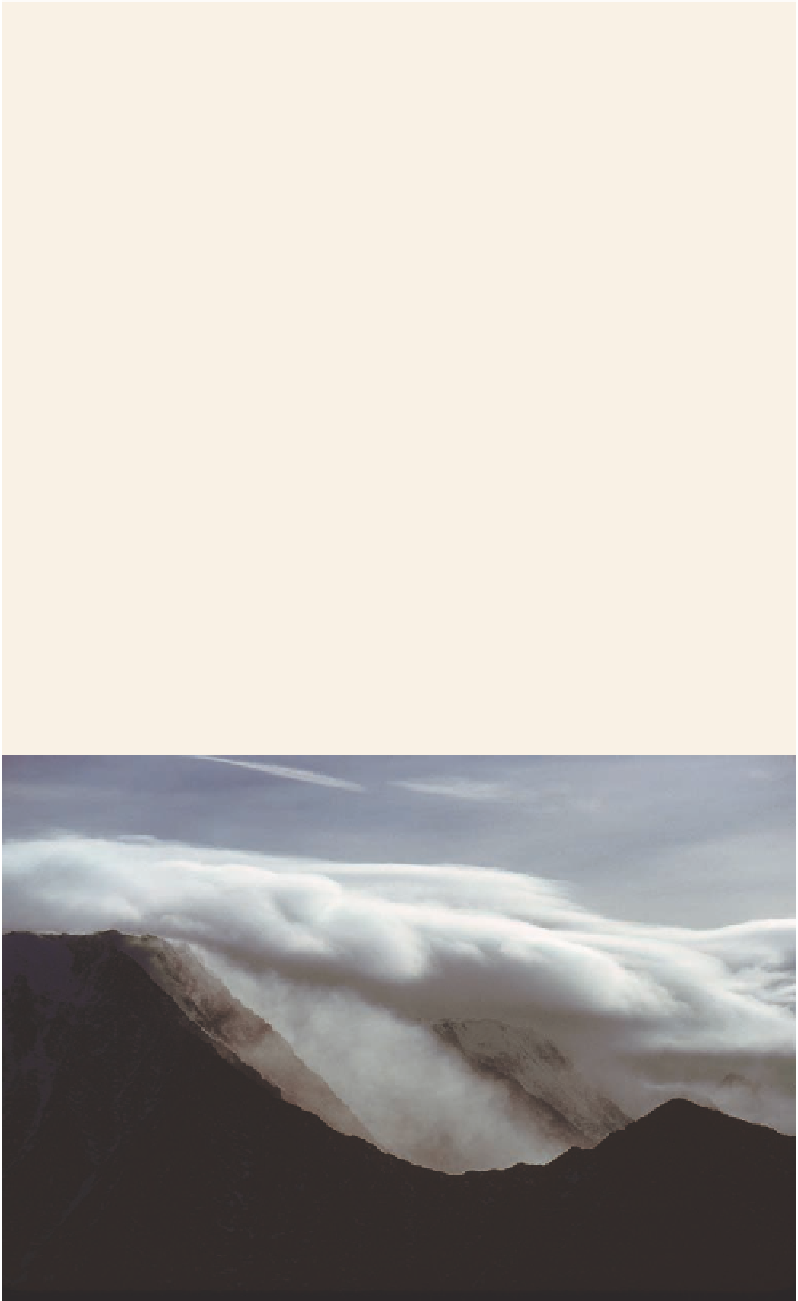

Figure S.11. A cloud layer

shoots out from the

escarpment lip of the La

Gorce Mountains. Beneath

it, a plume of snow traces

the dense, frigid, katabatic

wind as it leaves the preci-

pice and plunges into the

valley behind the interven-

ing ridgeline.