Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

*

other Clitellata

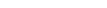

FIGURE 3.1

Simplified phylogenetic tree of major groups of earthworms. The node with the asterisk is the

polytomy discussed in detail in the text. (After Jamieson et al. 2002.)

To provide an example with biogeographic relevance, the Glossoscolecidae (South America)

are clearly a sister group of the Eudrilidae (Africa) rather than allied to the Microchaetidae (Africa),

as presented by Bouch (1983) and Omodeo (1998). The Lumbricina of Omodeo and similar

concepts of other groups emerged relatively intact but with significant modifications, particularly

the possible inclusion of the Eudrilidae. This remains unclear because a probable trichotomy of

Megascolecoidea (M), Lumbricoidea (L), and Glossoscolecidae plus Eudrilidae (G) was unresolved

by Jamieson et al. (2002) and could be resolved in three different ways: (M, (L, G)); ((M, L),G);

or ((M, G), L). Like Omodeo (2000), one could resort to paleogeography to support a phylogenetic

theory, choosing the last of the three because this leaves the Gondwanan taxa sharing a more recent

common ancestor than with the primarily Laurasian Lumbricoidea. However, this was not the

conclusion reached by Omodeo (1998), who placed the Glossoscolecidae with the Lumbricoidea,

nor is it consistent with the work of Bouch (1983), who placed the Glossoscolecidae with the

Microchaetidae, Kynotidae, and Almidae as the Glossoscolecoidea, leaving the Eudrilidae with the

Megascolecoidea. What is needed is to expand the taxon sampling (see

Zwickl and Hillis

2002)

of Jamieson et al. (2002) to include more Lumbricoidea, Glossoscolecidae, Ocnerdrilidae, and

Eudrilidae to resolve the polytomy and to address more definitively OmodeoÔs (1998) polyphyletic

model of earthworm evolution. This should also include some species of Alluroididae, because that

family is proposed as the source of two independent ancestors of major trunks of the Crassiclitellata

tree (Omodeo 1998).

Another problem is that some versions of the distribution of Lumbricoidea have members (the

Microchaetidae) located in sub-Saharan Africa. Can this indicate that earthworms have a significant

pre-Pangaea history, such that their biogeography can be understood only with reference to two

cycles of continental fragmentation? Clearly, this issue cannot be settled until the proposed phy-

logeny can be stabilized, but some pre-Pangaea reconstructions link continental geologic units that

are now far apart, such as northeastern North America and South Africa. Although geological

models of earth evolution can provide some corroboration of phylogenetic hypotheses, the main

burden of gathering evidence lies with biologists. I now consider the contributions of biological

data to understanding geological events.