Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

21.2.5.1

Erosional forms

to: (1) the shifting and overturning of the rock, particu-

larly if it is small, and (2) bidirectional or multidirectional

winds (Figure 21.10(b)). If the rock is large and stable, it

provides an excellent indicator of regional wind direction.

One of the more common features recorded for ven-

tifacts is smoothing and

polishing

of the rock surface,

both on the facets and within the flutes and grooves (Max-

son, 1940). The sheen on ventifacts in periglacial settings

may exceed that of glacial polish (Tremblay, 1961). The

retention of polish over time varies according to rock type

(Clark and Wilson, 1992). Although ventifact surfaces are

macroscopically smooth, scanning electron micrographs

(SEMs) at high magnifications reveal considerable topo-

graphic roughness and surfaces covered with microcrack-

ing or cleavage fractures formed by repeated chipping by

sand grains (Laity, 1995; Laity and Bridges, 2009). Af-

ter abrasion ceases, rock coatings such as silica glaze or

desert varnish may cover the surface (Dorn, 1995).

While small rocks usually have both polish and

facets, larger boulders are covered by additional features,

Unlike desert depressions or yardangs, which develop by

several interacting processes, usually involving both water

and wind, the sole mechanism of mass removal in ven-

tifacts is abrasion (although weathering in between ero-

sional episodes may alter surface characteristics). Abra-

sion has the potential to form one or more of several key

features on a ventifact, depending on the rock type and size

and duration of exposure: facets, polish (similar to glacial

polish) and features (pits, grooves, flutes and so on).

A

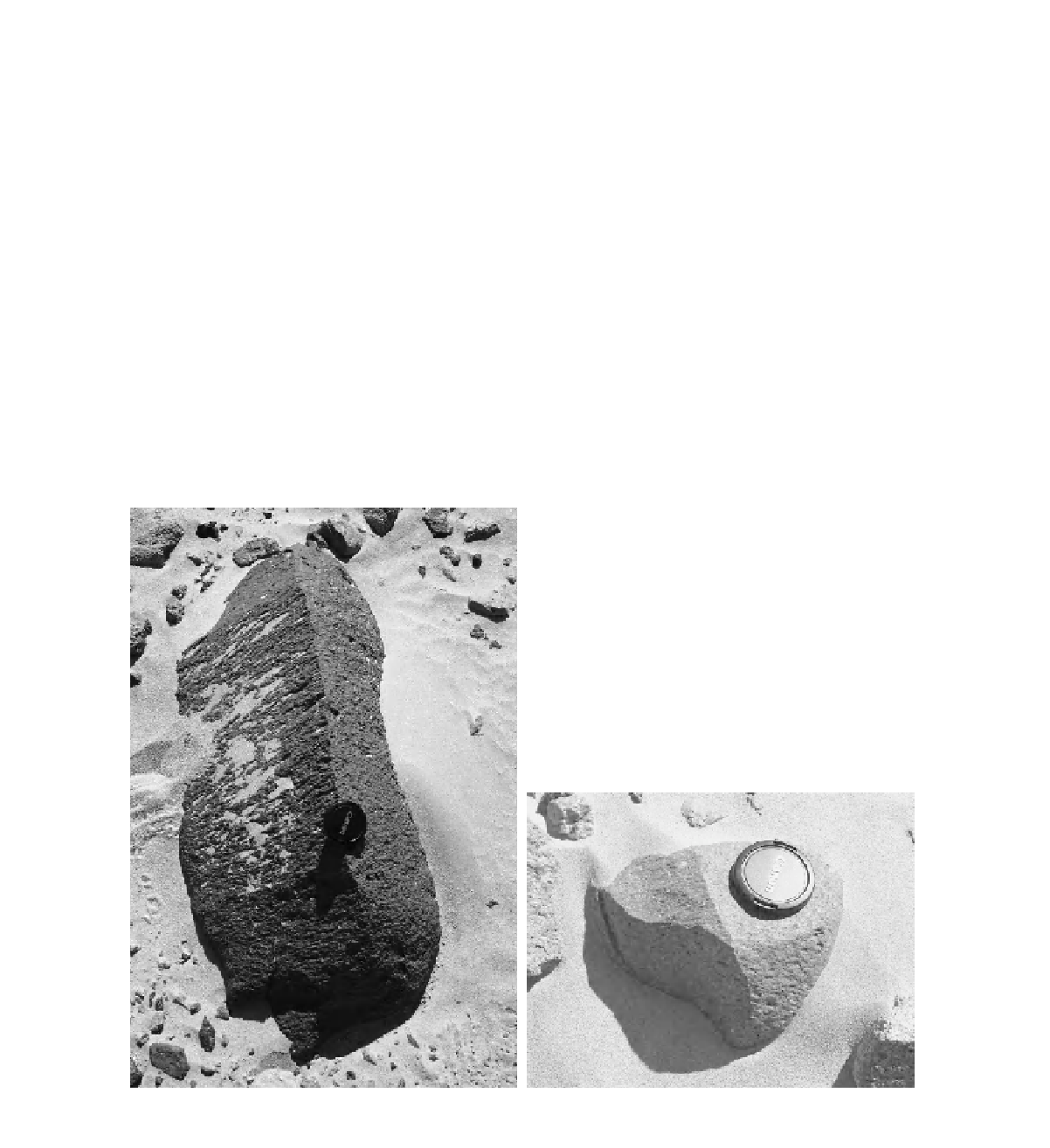

facet

is a planar surface that evolves at right an-

gles to the wind: ventifacts may develop more than one

facet, which often join along a sharp ridge or

keel

(Fig-

ure 21.10(a)). The number of keels (kante) has been

used to describe small ventifacts as einkante, zweikanter,

dreikanter (one-, two-, three-ridged) and so on (Bryan,

1931). Much early research was devoted to the morpho-

logical classification of ventifacts (Bryan, 1931; King,

1936; Czajka, 1972). Multiple facets develop in response

(a)

(b)

Figure 21.10

(a) Basalt ventifact with a single keel, formed by bidirectional wind flow in the Owens Valley, California. The

surface with the lower facet angle shows lineations perpendicular to the keel, whereas the higher angle facet is largely pitted.