Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

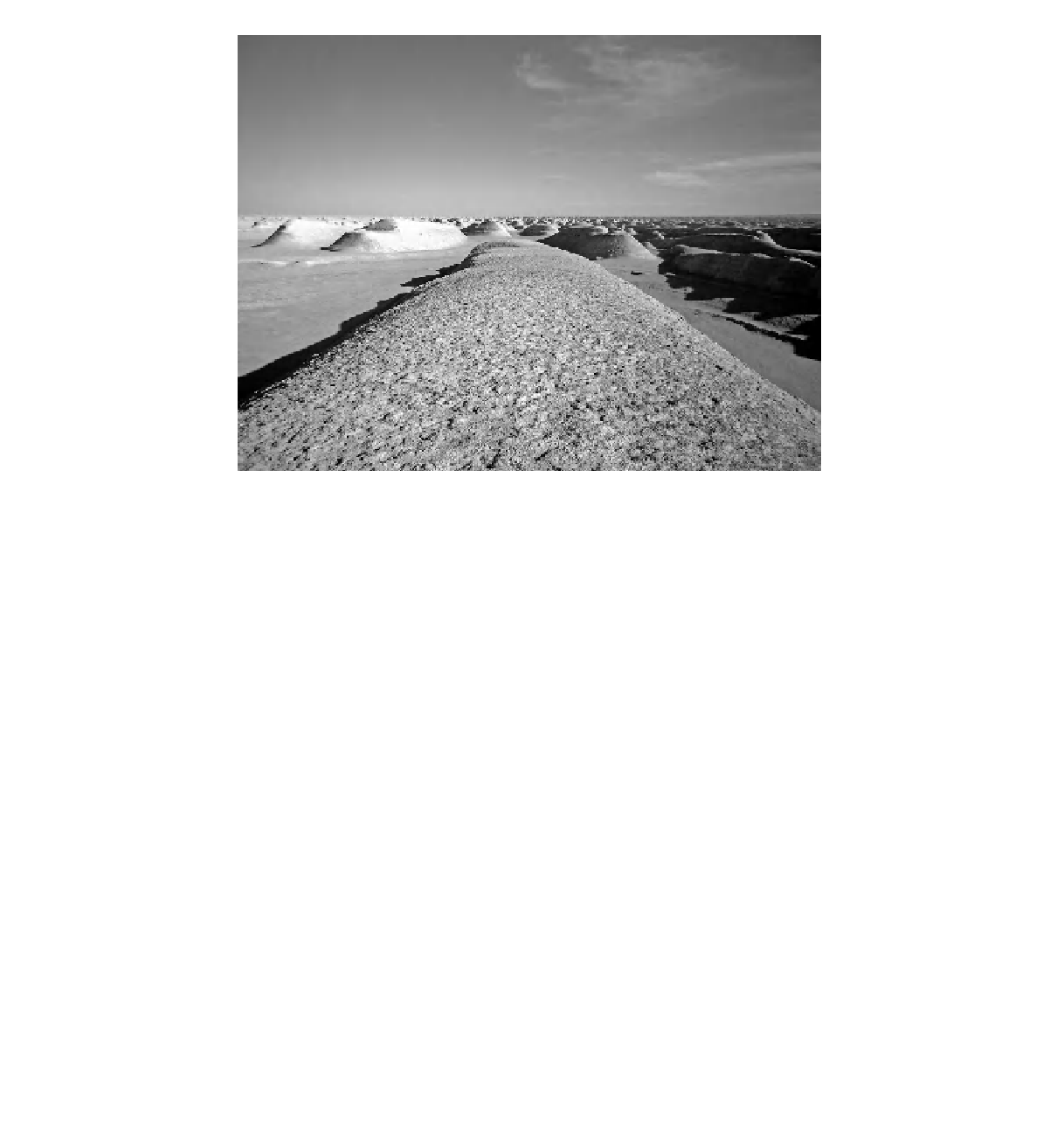

Figure 21.9

Megayardangs of the Qaidam basin, capped by a salt crust, occur in a vast swarm (photo courtesy of R. Heermance).

21.2.4

Inverted topography

lief within yardang swarms on the limestone plateau in

the Western Desert of Egypt. Inverted relief in the Bodele

Depression, Chad, is interpreted as a deltaic distributary

system (Bristow, Drake and Armitage, 2009), exposed by

up to 4 m of deflation.

A landscape develops inverted relief when previously low

areas, such as river channels, are left standing in relief by

wind erosion at later stages of climatic and topographic

development. There is little detailed documentation of

this landform and therefore this section will largely be

inventory examples of these landforms. In deserts, chan-

nels are commonly more resistant than the surrounding

rocks owing to induration by chemical precipitates. In the

intensely arid south coast of Peru, for example, the du-

racrete enrichment of palaeochannels causes them to stand

in relief on deflated terraces (Beresford-Jones, Lewis and

Boreham, 2009). The best-studied inverted relief is the

Plio-Pleistocene raised channel systems of the western

Sharqiya (Wahiba), Oman. On the western edge of the

Wahiba Sands, these complex high-standing palaeochan-

nel systems cross alluvial fans that have been extensively

lowered by deflation (Maizels, 1987).

Inverted relief is most commonly found within yardang

fields. In the yardang landscape of the Lop-Nor basin,

China, former river courses with resistant silty beds are

inverted and marked by ridges and remnant hillocks

(Horner, 1932), whereas soft, young sediments have been

eroded away by the wind. Similarly, in the hyper-arid re-

gion south of Dakhla, Egypt, intense aeolian erosion has

brought exhumed meander scrolls into sharp relief and

cut them into yardang fields (Brookes, 2003b). Whitney

21.2.5

Ventifacts

Ventifacts are wind-eroded rocks, characterised by their

distinctive morphology and texture. They are found in

periglacial, coastal and desert settings -environments

with an ample supply of abrasive particles, limited

vegetation cover and strong winds (Laity, 1994, 2009).

Many ventifacts, particularly in periglacial and desert

regions, are fossil in nature, the product of earlier surface

and climatic conditions. Relict ventifacts commonly

appear weathered, dulled, stained, lichen-covered or

partly exfoliated (Blackwelder, 1929; Smith, 1967,

1984), darkened by rock varnish or covered by patches

of grooved and fluted surfaces, with intervening areas

eroded by weathering loss (Powers, 1936).

Research into ventifacts, which had been sporadic in

the past, has gained momentum in recent years (Knight,

2008; Laity, 2009; Bridges

et al.

, 2010). Ventifacts are

seen not as mere geological curiosities but as a link in

understanding sediment movement and climate change, as

part of a larger continuum of aeolian studies and as a proxy