Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

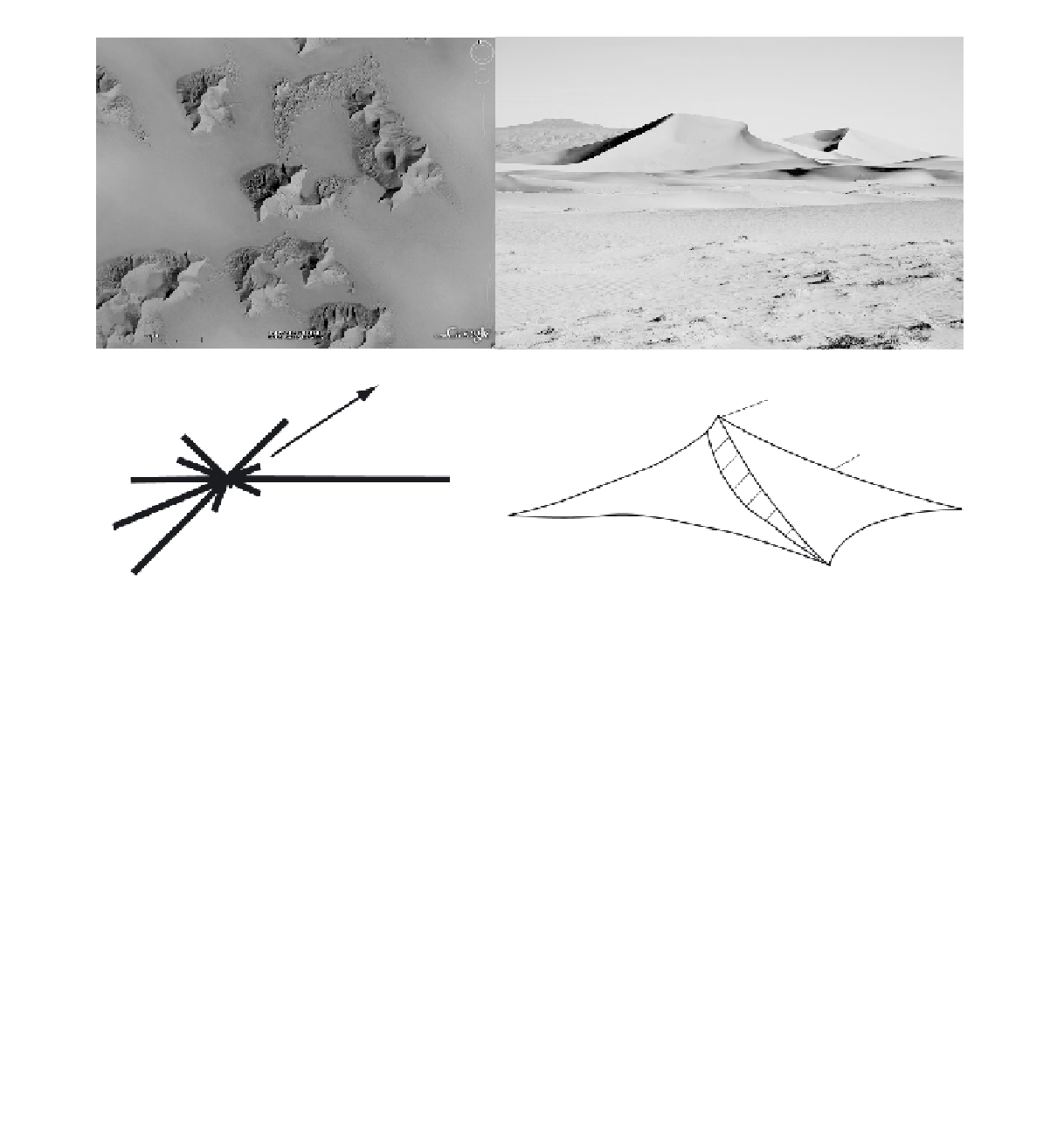

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Crest

Arm

Plinth

Eastern Namib Sand Sea

RDP/DP = 0.25

Figure 19.6

Star dunes: (a) clusters of star dunes, eastern Rub al Khali, Saudi Arabia; (b) Silver Peak, Nevada; (c) wind regime

of star dunes; (d) anatomy of star dunes.

apart (Bullard

et al.

, 1995; Fitzsimmons, 2007), with a

length of 20-25 km. The ridges may join in Y-junctions.

Several varieties of this pattern can be identified (Figure

19.6), related to sand supply, distance from sand sources,

vegetation cover and persistence of dune-forming winds

(Bullard

et al.

, 1995; Wasson

et al.

, 1988).

Compound linear dunes (Figure 19.5(a) and (b)) con-

sist of several narrow, closely spaced (100-200 m) seif-

like ridges on the crest of broad linear plinths, which are

spaced as much as 2.5 km apart. Good examples occur in

the southern Namib Sand Sea (Lancaster, 1989c) and the

Fachi Bilma Erg in Niger (Mainguet and Callot, 1978).

Complex linear dunes (Figure 19.5(c) and (d)) are com-

prised of relatively straight, continuous, linear ridges on

which other dune types are superimposed. Such dunes

are typically spaced 1-2.5 km apart and reach heights of

50-250 m. Complex linear dunes in the Namib Sand Sea

and Saudi Arabia consist of a sinuous main crestline with

superimposed crescentic dunes on the dune flanks (Lan-

caster, 1989c; Livingstone, 1993). In places, the crest line

may consist of a series of peaks similar to star dunes sep-

arated by lower sinuous sharp crest lines. Such complex

areas (e.g. the eastern Namib Sand Sea and southeastern

parts of the UAE).

The origins of linear dunes and their relationship to

formative wind directions have been the subject of con-

siderable debate (Lancaster, 1982b; Livingstone, 1988;

Tsoar, 1989). A substantial body of empirical evidence

now indicates that linear dunes form in bidirectional

wind regimes with the two modes separated by 90

◦

or

more. This includes correlations between the occurrence

of linear dune and information on the directional vari-

ability of wind regimes in these areas (e.g. Fryberger,

1979): studies of internal sedimentary structures (Bris-

tow, Bailey and Lancaster, 2000; McKee, 1982; McKee

and Tibbitts, 1964), experiments in flumes (Reffet

et al.

,

2008; Rubin and Ikeda, 1990) and numerical simulations

(Werner and Kocurek, 1997), as well as detailed process

studies on linear dunes (Livingstone, 1986, 1988, 1993;

Tsoar, 1983). Models for linear dune formation that invoke

boundary layer roller vortices in which helicoidal flow

sweeps sand from interdune areas to dunes (Hanna, 1969)

are not generally supported by empirical data - evidence

for the occurrence of such boundary layer structures is