Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

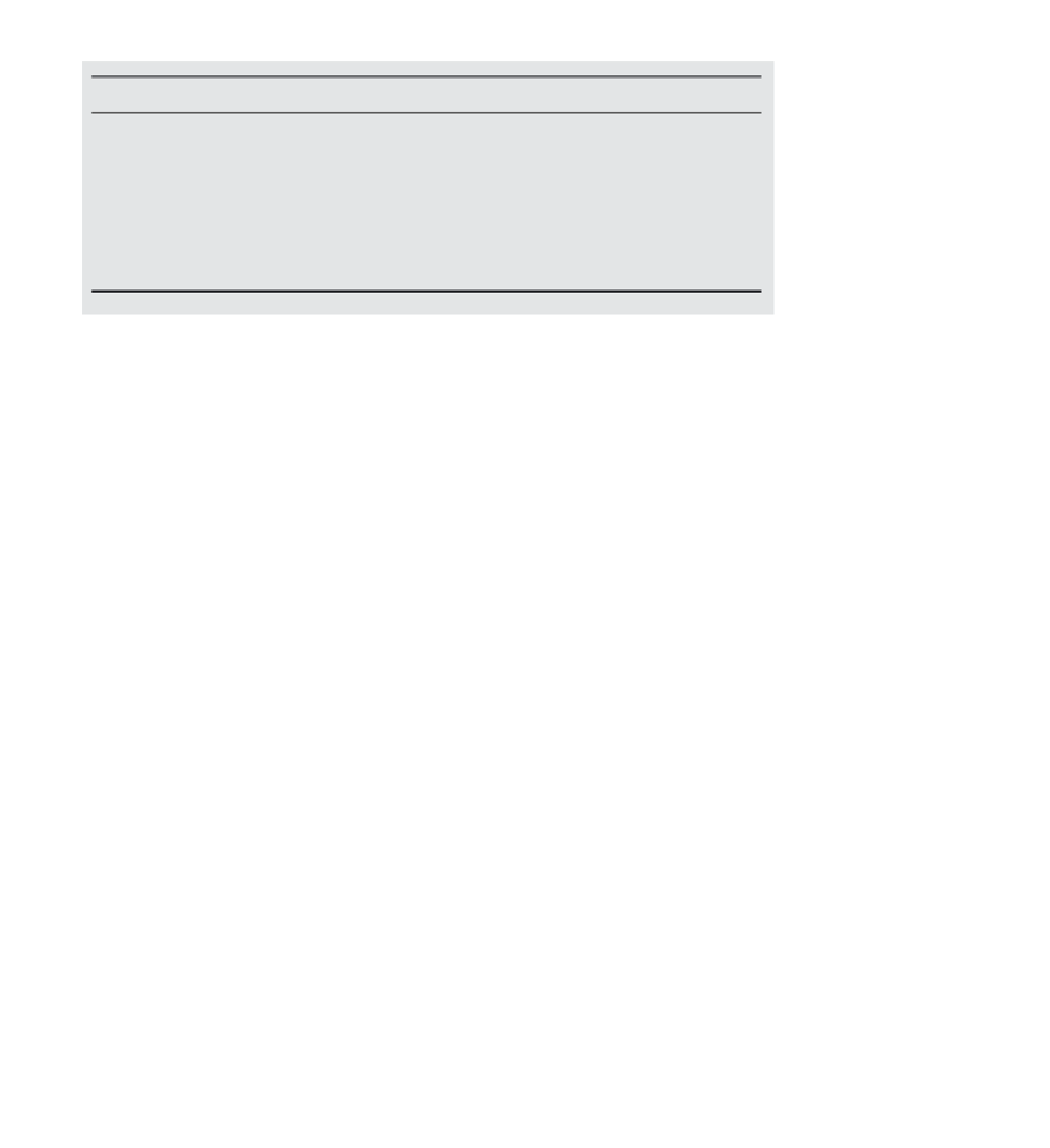

Table 3.2

Some possible differences between active and ancient aeolian sands.

Active sands

Ancient sands

95 % of particles are sand-sized

Bimodal or unimodal size distribution

Larger particles more rounded

Bedding structures are often present

Low carbonate content

Higher components of 'fines' due to subsequent

inputs or weathering

May be altered by post-depositional inputs/losses

Rounding may be reduced by post-depositional

chemical weathering

Structure destroyed by burrowing animals and plant

root growth

Carbonate contents increased through organic inputs

sedimentology' relies on the same uniformitarian princi-

ples that are applied in the interpretation of relict land-

forms, and suffers the same problems. Particularly im-

portant are the effects of post-depositional modification

(diagenesis), which can alter or masque important diag-

nostic characteristics.

Aeolian deposits in both marine and terrestrial contexts

can be identified by a range of sedimentary characteris-

tics (Table 3.2), though these may be altered significantly

after deposition. At Didwana in the Thar Desert, India,

for example, a

(Thomas, 1987c). This is because sedimentary character-

istics can be inherited from preceding phases of deposition

and reworking, or even from parent sediments. The same

applies to reddened dune sands, which have sometimes

been assumed to indicate aeolian stability and humidity

(see Gardner and Pye, 1981) or other aspects of dune

landscape history (Bullard and White, 2005). Therefore

aeolian attributes in a sediment do not necessarily indi-

cate that aeolian processes were the last mechanism of

deposition.

Evaporite deposits are an important component of many

arid and semi-arid basin environments (see Chapter 9) and

the coastal sebkhas of some arid regions (Glennie, 1987).

Lowestein and Hardie (1985) identified a three-stage cy-

cle of ephemeral-playa sedimentation that results in the

modification of a salt-crystal structure through dissolu-

tion and redeposition and the alternation of mud and salt

layers. The sequences they identify in modern playa sed-

iments are also identifiable in the sedimentary record and

have assisted in the environmental interpretation of playa

deposits preserved in the Quaternary record (see, for ex-

ample, Hunt and Mabey, 1966; Smith

et al.

, 1983).

Although the minerals within playa salt deposits are

somewhat dependent upon the chemistry of inflowing wa-

ters (Lowestein and Hardie, 1985), differences in evapor-

ite deposits can yield information about the degree of

salinity and hence evaporation rates during past peri-

ods of playa sedimentation (Ullman and McLoed, 1986;

Risacher and Fritz, 2000). Bromide and chloride con-

centrations may be particularly valuable in this respect

(Allison and Barnes, 1985; Ullman, 1985). Oxygen and

carbon isotope ratios from lacustrine sediments may also

yield useful information though applications may be

more restricted than from ocean sediments (Stuiver, 1970;

Gasse

et al.

, 1987; Liu

et al.

, 2009). Lowenstein

et al.

(1994) have analysed the fluid inclusions in halite from

a 15 m lake sediment core extracted from the Qaidam

20 m high section in aeolian sands, di-

agnosed by their sedimentary structures and sedimento-

logical characteristics, exposed in a canal cutting indicates

that multiple periods of aridity have occurred since 190ka,

the basal luminescence date Singhvi

et al.

, (2010). In the

United Arab Emirates, quarrying of mega sand dunes has

exposed the complex internal structure of dunes of over

60 m thickness. When subject to OSL dating, these reveal

the long, and punctuated, records of aeolian accumulation

that have occurred in the region during the late Quater-

nary (Figure 3.2). In other contexts, road cuttings (Figure

3.3) and occasional natural exposures reveal dune inter-

nal structures that aid record interpretations. However, in

many studies, lack of internal exposures means that sam-

pling for dating and analysis, via drilling (Figure 3.4),

is done 'blind', thus limiting interpretation purely to the

ages that are obtained by applying luminescence dating

(see Chapter 17) and the properties of the sediments them-

selves. The use of ground penetrating radar may, however,

in some contexts assist in overcoming this problem, as

it may reveal the structures with dune bodies (Bristow,

Lancaster and Duller, 2005).

Interpreting the environmental significance of sand

with aeolian attributes is not necessarily simple (e.g.

Fitzsimmons, Magee and Amos, 2009). In the Kalahari,

the sands found not only in conjunction with relict aeo-

lian landforms but also with those of lacustrine and fluvial

∼