Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

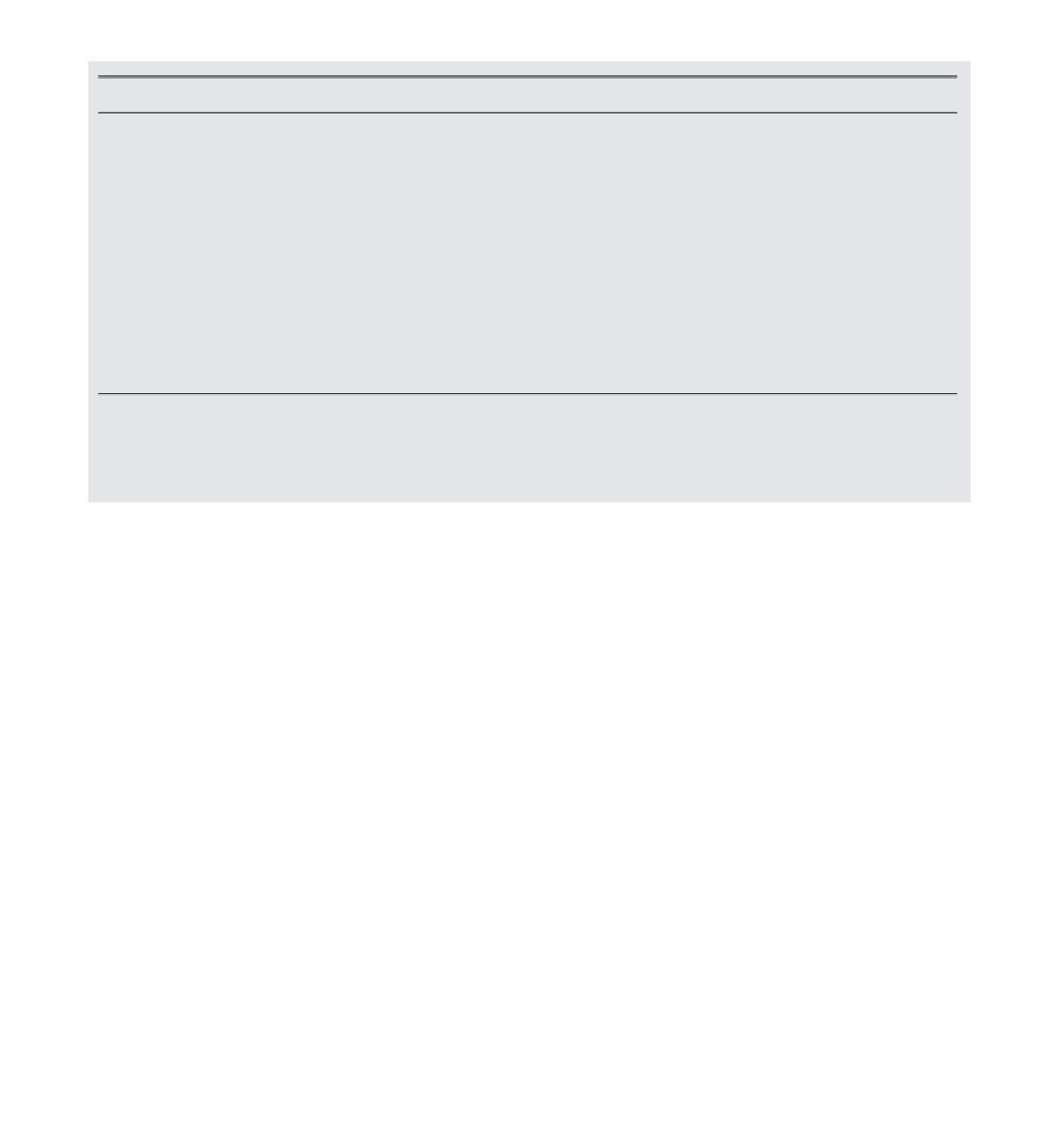

Table 13.1

Attributes of endogenous desert ephemeral streams and rivers.

Upland, headwater channels

a

Lowland, distal channels

b

Attribute

Small to medium, regional;

<

1

0

-10

3

km

2

Large to subcontinental, 10

5

km

2

System size

Terrain

Mountainous, rifted or block-faulted

Peneplaned and cratonic

Moderate to high; 10

−

3

-10

−

2

Low; 10

−

4

Channel slope

Channel type

Single-thread (often straight), braided

Anastomosed, braided, single-thread

Flow regime

Ephemeral; predominantly upper flow regime

Intermittent and ephemeral;

predominantly lower flow regime

Flood timebase

10

0

-10

2

h

10

2

-10

3

h

Sediment concentration:

(a) Suspended load

(b) Bedload

High to very high; 15-285 g/L

High; maximum recorded: 5 g/L (7 kg/m s at a

boundary shear stress of 36 Pa)

Low to moderate; 0.5-12 g/L

Unknown

Bedforms in sand

Plane bed (predominant); dunes (occasional)

Ripples (20-30 %); dunes (25-45 %);

plane bed (7-15 %)

a

Alexandrov

et al

. (2009); Bull (1979); Dunkerley (1992); Frostick, Reid and Layman (1983); Graf (1983); Hassan (1990b); Karcz (1972);

Laronne and Reid (1993); Leopold, Emmett and Myrick (1966); Meerovitch, Laronne and Reid (1998); Powell, Reid and Laronne (2001); Renard

and Keppel (1966); Schick, Lekach and Hassan (1987); Schumm (1961); Sharma and Murthy (1994); Sneh (1983); Thornes (1977).

b

Bourke and Pickup (1999); Maroulis and Nanson (1996); Nanson and Knighton (1996); Tooth (2000); Tooth and Nanson (2004); Williams

(1971).

1967; Williams, 1971; Sneh, 1983), though some are less

specific (such as Picard and High, 1973).

Before assessing what lessons might be gleaned from

the present in order to interpret ancient desert fluvial sed-

iments, it is essential to remind ourselves that research on

modern arid-zone rivers has been conducted largely in two

distinct morphogenetic provinces. The first (and probably

most visited) might be characterised as headwaters, in-

volving small- to medium-sized catchments. Much of this

research has been conducted in or near orogens or rifts of

Cenozoic age and comes from the American southwest,

the Levant and Maghreb, Iberia, East Africa and north-

west India. The second emanates from cratonic lowlands,

often involving distal reaches of systems of regional to

subcontinental scale. Most of this research has been car-

ried out in Australia, though some is located in southern

Africa. Table 13.1 attempts to summarise key attributes

of the drainage systems in these two provinces. Nanson,

Tooth and Knighton (2002) have issued a strong caution

that the riverine processes and landforms of montane and

rifted terrains might only be of marginal relevance when

characterising and understanding systems in cratonic ter-

rain. It is axiomatic that the reverse is true. It behoves the

sedimentologist, therefore, to contextualise the geomor-

phological arena within which sediments were accumu-

lating, where possible keeping in mind that knowledge

about desert stream sediments is, as yet, in its infancy.

Since the hydraulic processes that entrain a clast are uni-

versal regardless of the environmental setting, the question

teristics that can be used to distinguish ephemeral from

perennial stream deposits. Some doubt has been cast (e.g.

North and Taylor, 1996; Martin, 2000). However, we con-

tend that there appear to be at least three attributes that

might especially lead a sedimentologist to conclude that

an ancient sedimentary sequence was laid down by an

ephemeral stream.

13.5.1

Thin beds

There is no quantification that can be used to justify a

claim that desert river deposits are composed charac-

teristically of thin beds, i.e. 0.1-0.3 m thick. However,

deposits of widely differing age - Devonian (Tunbridge,

1984) (Figure 13.26), Triassic (Frostick

et al

., 1988; Reid,

Linsey and Frostick, 1989) and Holocene (Frostick and

Reid, 1986) - undoubtedly have an easily recognis-

able affinity because of the nature of their bedding

(Figure 13.27). There is plenty of evidence of the mi-

nor incision that is associated with scour in the nested

fill-sets of ancient deposits and the range in bed thickness

is consistent with the depth of scour and fill as defined by

field experiments in modern sand-bed ephemeral streams

(Leopold, Emmett and Myrick, 1966; Powell

et al

., 2006)

(Figures 13.17 and 13.27). Modern gravel-bed ephemerals

also exhibit similar thicknesses of scour and fill (Laronne

and Shlomi, 2007; Lekach, Amit and Grodek, 2009).

Hassan, Marren and Schwartz (2009) (Figure 13.28) de-