Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

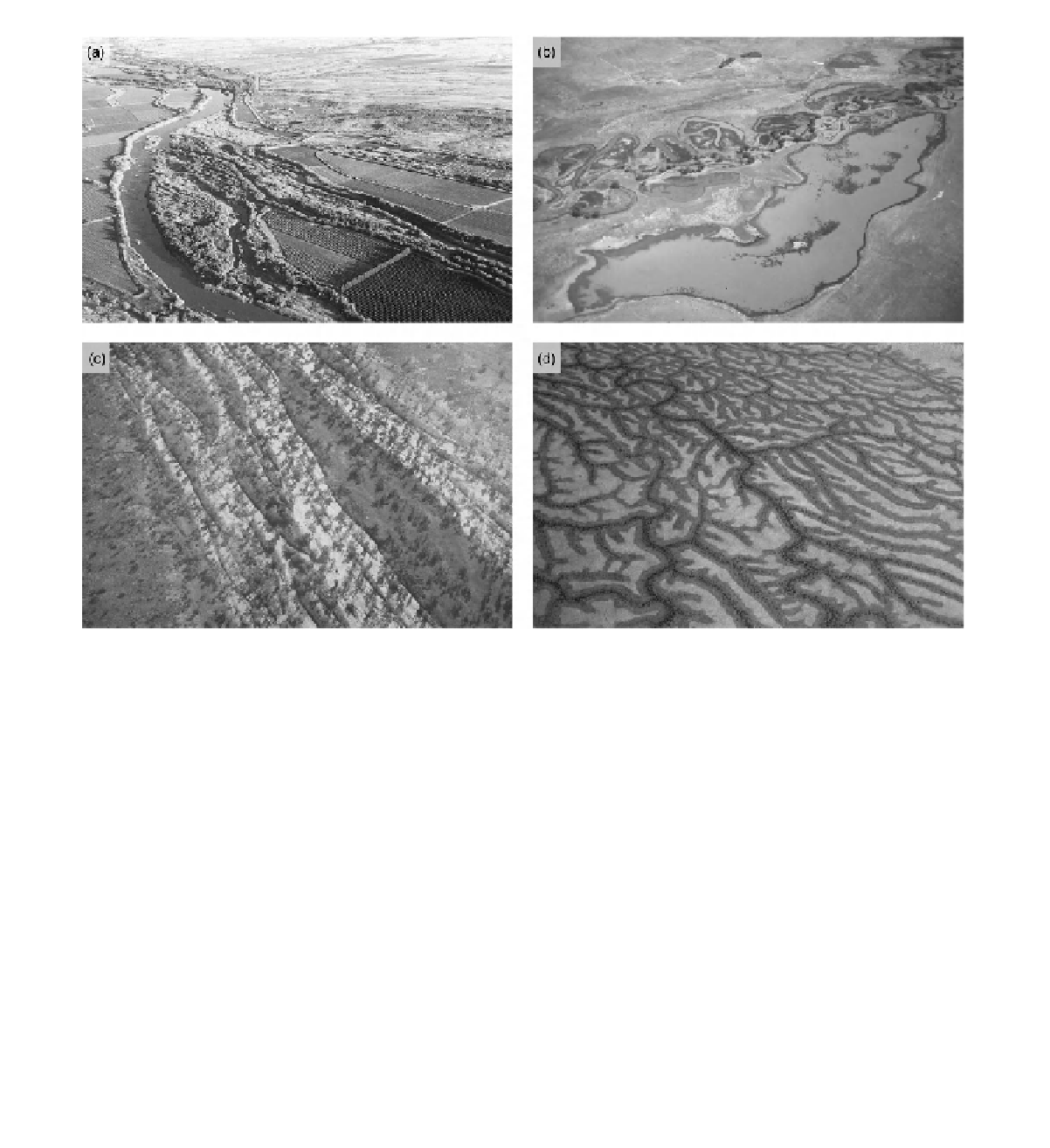

Figure 12.2

Oblique aerial views illustrating dryland rivers that contrast with many 'textbook' characteristics: (a) mixed

bedrock-alluvial anabranching on the Orange River, South Africa, illustrating a shallow valley with multiple channels that di-

vide and rejoin around large islands composed of alluvium and/or bedrock (flow direction from upper left to lower right); (b)

meandering on the Klip River, eastern South Africa, showing a sinuous channel (marked by invasive willow trees) flanked by

flooded oxbows and backswamps (flow direction from middle left to upper right); (c) alluvial anabranching on the Marshall River,

central Australia, illustrating multiple channels dividing and rejoining around vegetated, narrow ridges and broader islands (flow

direction towards lower right); (d) reticulate channels on the floodplains along Cooper Creek, eastern central Australia (general

flow direction from upper left to lower right).

generalisations about dryland river characteristics. In par-

ticular, studies of larger, lower gradient rivers draining

tectonically quiescent or tectonically inactive catchments

in Australia and southern Africa have served to empha-

sise how many dryland rivers exhibit processes, forms and

behaviours that contrast sharply with the 'textbook' char-

acteristics of dryland rivers (Figure 12.2). The extensive

anabranching, anastomosing and meandering rivers that

are characteristic of some parts of these drylands, for ex-

ample, challenge the common assumptions that braided

rivers are most common in drylands and that meander-

ing rivers are rarely developed, and also demonstrate how

some dryland rivers may exhibit forms, processes and be-

haviours that are similar to humid rivers, including aspects

1986; Nanson

et al.

, 1988; McCarthy and Ellery, 1998;

Knighton and Nanson, 1994a, 1997, 2000; Tooth, 1999;

Tooth and Nanson, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2004). Recent

overviews have drawn attention to the global diversity

of dryland rivers and have highlighted the greater over-

lap with rivers in other climatic settings (Nanson, Tooth

and Knighton, 2002; Powell, 2009), but these messages

have tended to become lost among the far more numerous

studies of rivers in small, steep, commonly tectonically

active catchments. For instance, in the most recent edited

volume on dryland rivers (Bull and Kirkby, 2002), the

thrust and balance of the chapters is focused largely on

catchments in the Mediterranean region (including Israel)

and the American southwest, which tend to conform to