Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

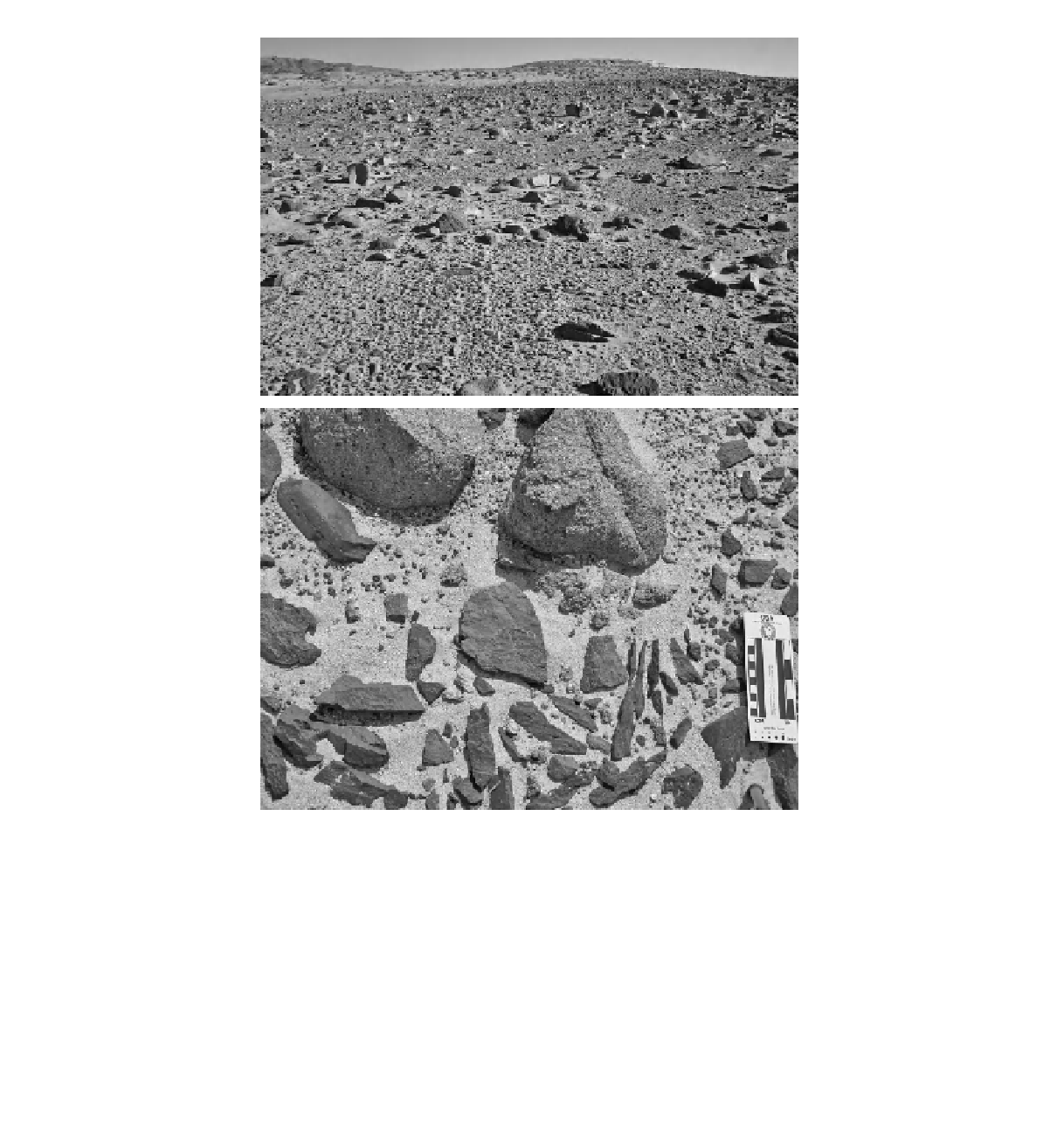

(a)

(b)

Figure 9.5

(a

)

This surface shows the transition from a hamada to a pavement south of Owens Lake, California. Many weathered

and wind-abraded boulders remain amid surface pebbles whose clast cover ranges from

∼

50 to 70 %. (b) Salts blown in from the

exposed saline surface of Owens Lake are actively weathering the rocks shown in Figure 9.5(a). The granular disintegration of

granites (upper two large rocks) and the angular splitting of fine-grained rocks (darker material) result in smaller clasts, which

over time may form an interlocking pavement.

9.3.3

Upward migration of stones

the stones are displaced upwards to the surface. This pro-

cess is believed to be significant in the stony tablelands of

Australia (Jessup, 1960; Twidale, 1994; Thomas, Clarke

and Pain, 2005). Laboratory experiments indicate that al-

though some upward movement of particles is possible,

partial burial may occur also by displacement (Cooke,

1970).

The upward migration of gravel is potentially less ef-

fective in other geographic regions. In the Mojave Desert,

The absence of stones beneath a desert pavement has been

accounted for by an upward migration of gravel through a

clay-rich B-horizon via alternating shrinking and swelling

associated with wetting and drying and/or freezing and

thawing (Springer, 1958; Jessup, 1960; Cooke, 1970;

Mabbutt, 1977). Soils that exhibit shrink-swell tenden-

cies contain expansive clays and swell and heave on wet-