Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

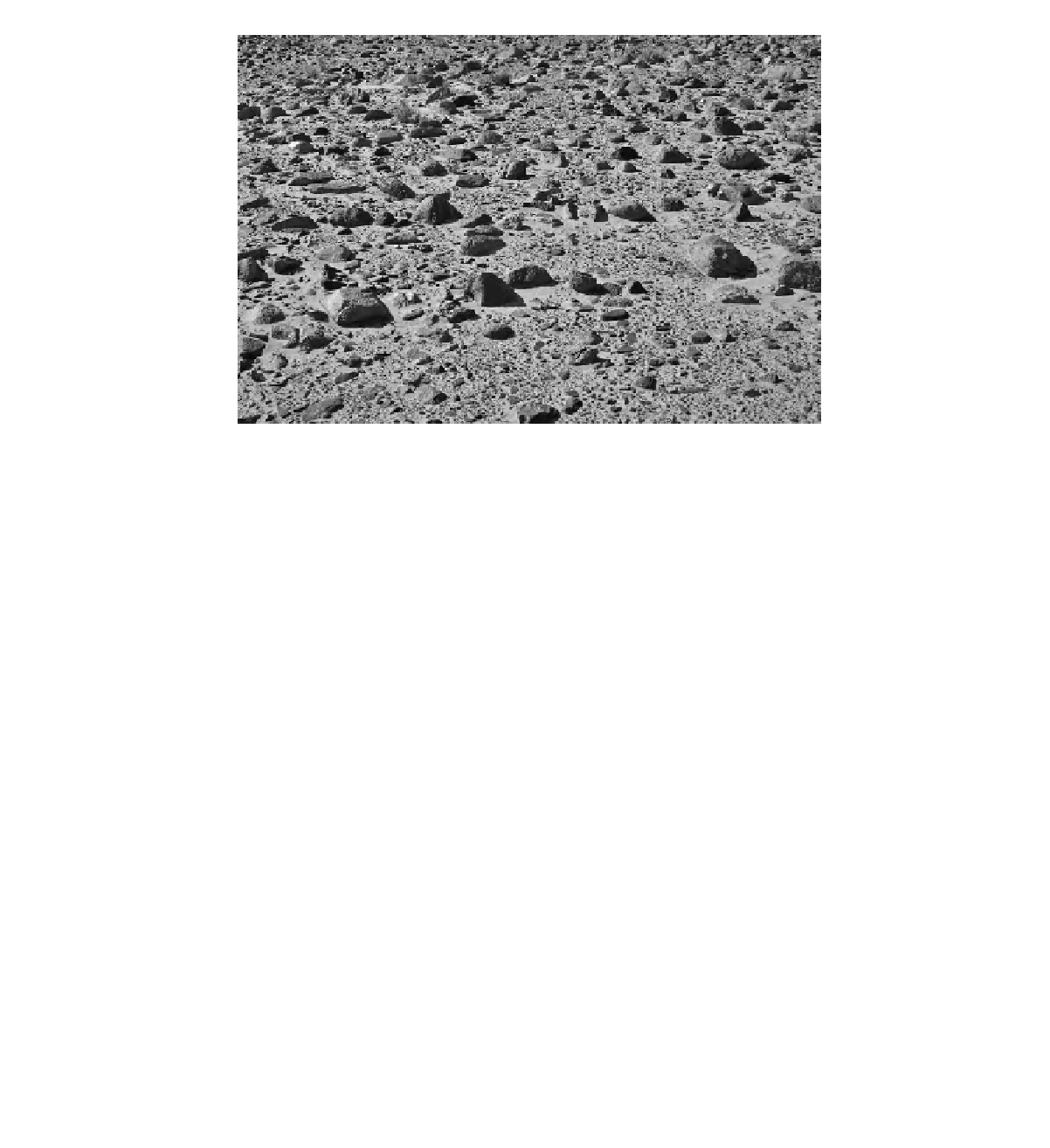

Figure 9.2

Boulder hamada to the east of the Sierra Nevada, California. The boulders were transported short distances from

nearby mountains and then isolated from further fluvial activity by faulting along the southern margin of Owens Lake. The boulders

have become more angular over time from abrasion. The hamada, mantled by loose sand, is transitional to a developing pavement.

of rounding and texture, development of desert varnish,

substrate, age and the degree to which the particles in-

terlock. Furthermore, many gravel mantles, although dif-

fering in name, share enough characteristics that they are

essentially of the same type. Thus, a 'pavement' in one

region may be a 'serir' in another. Conversely, there may

be significant differences in form or developmental his-

tory that are not yet fully understood. This section will

summarise what is known about these different named

surfaces. Following this initial regional examination, the

most widely studied of these types, the desert pavement,

will be examined in more detail.

section, is filled with a very thick sequence of gravel beds

(Mengxiong, 1994). Much of the rain and melting snow

and ice from the mountains disappear into these gravel

sequences. In piedmont areas, removed from the presence

of sand, the gravel cover may reach 100 % (Figure 9.3). In

recent deposits, the surface clasts retain a rounded form

and soil is absent.

Many Chinese dune fields are surrounded by gobi sur-

faces. One general theory for pavement formation is that

it represents a deflationary lag. Although this idea has

been largely discredited for accretionary desert pavements

in southwestern North America and elsewhere (see the

discussion later in this chapter), deflation may play a

role where both gravel and sand are present, including

some gobi.

To date, there appears to be little research on the nature

of gobi in central Asia. My own brief travels suggest at

least three types of gravel surfaces: (1) fresh, relatively

unmodified gravel surfaces with rounded fluvial clasts;

(2) gobi in sandy environments (potentially 'deflationary

gobi', but not yet properly documented); and (3) well-

knit, varnished pavements, with smoothed surfaces and

an underlying stone-free and silty substrate, similar to ac-

cretionary stone pavements of southwestern North Amer-

ica. The unmodified gobi occur where active storms and

flooding bring gravel from the mountains on to the pied-

mont surfaces: the gravels and cobbles are well rounded

and largely unvarnished, and lack the silt-rich subsurface

9.2.2.1

Gobi

The term 'gobi' is Mongolian, referring to a region of

flat gravel pavement (Wang

et al.

, 2006) that forms the

basis of the Gobi Desert. In Mongolia, 14 % of the land is

desert, with surfaces extensively covered in gravel (Yang

et al.

, 2004). 'Gobi' is also used in arid parts of China (Li

et al.

, 2006), where vast expanses of unvegetated gravel

plains occur (Figure 9.3). In northern China, gobi covers

about 44 % of the desert (Yang

et al.

, 2004).

Gravel-covered regions are further subdivided into gobi

of accumulation and gobi of denudation (Yang

et al.

,

2004), but these terms are not clearly defined. 'Gobi

of accumulation' appears to refer to the extensive pied-

mont plains that cover the inland Quaternary basin sur-