Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

timescales over which this occurs can be studied using

several dating methods. Continuing accretion in carbon-

ate horizons can result in their upper surface progres-

sively approaching the ground surface, over substantial

fractions of Quaternary time. These time-related develop-

ments have been studied with a view to using the depth

and thickness of carbonate layers to estimate the age of

desert surfaces within which such accumulations occur

(e.g. Marion, 1989). The voluminous carbon storage in

soil carbonates of the drylands is a significant component

of the global carbon cycle (Kraimer, Monger and Steiner,

2005), and this provides yet another example of the way

in which desert soils exert an influence that extends well

beyond the drylands themselves.

The detailed history of most desert soils remains un-

known, and is likely to be complex. However, the present-

day morphology of such soils has been studied in greater

detail. We will turn now to consider some of the key

morphologic features found in many desert soils that are

important in setting their place in the hydrologic and

geomorphic functioning of the landscape. The features

present often constitute a mixture of ages, some being

rather young and some quite old. Desert soils are truly

features that are

polygenetic

, forming a palimpsest of past

events.

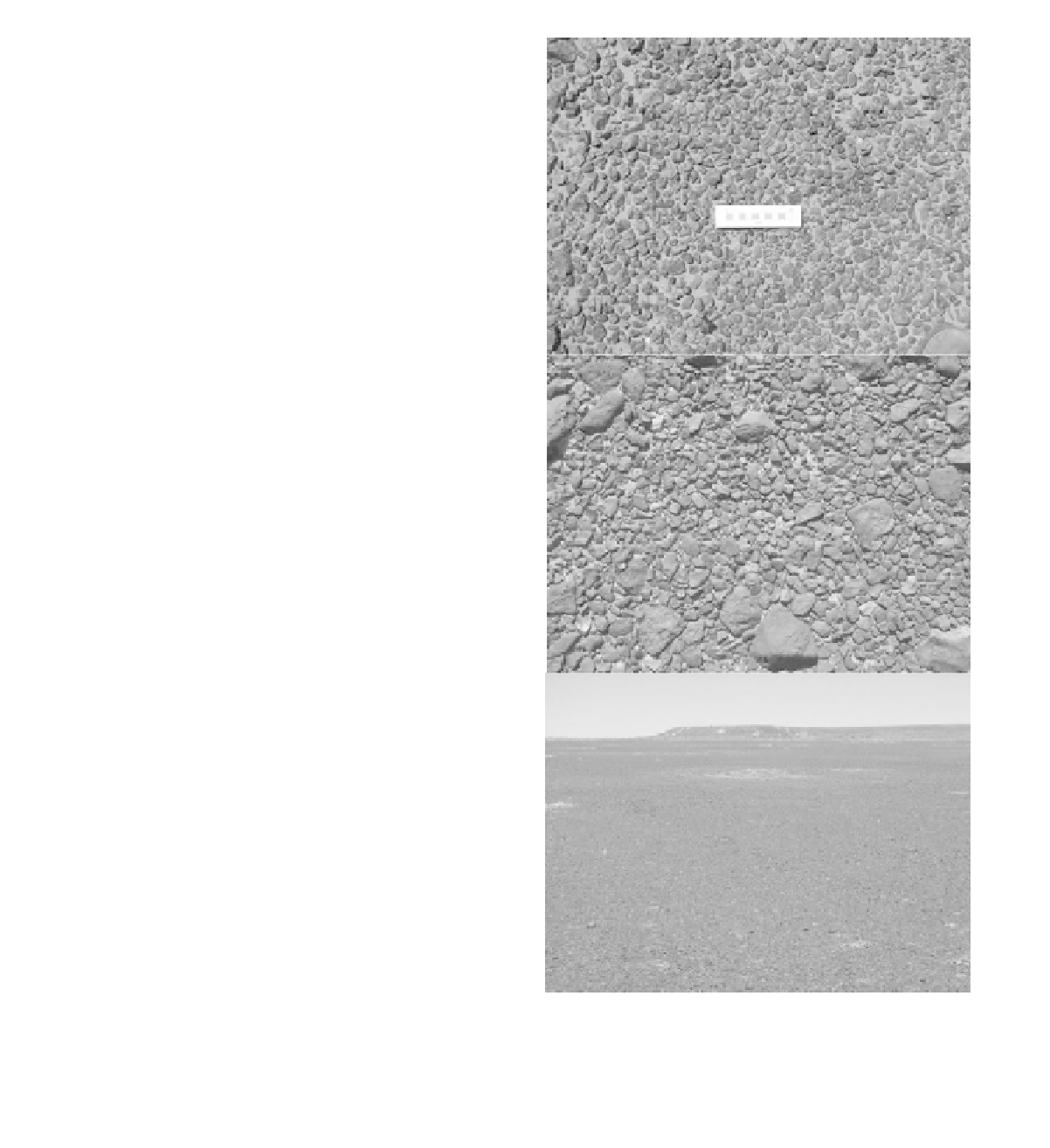

(a)

(b)

7.4

Stone-mantled surfaces and

desert pavements

(c)

Many desert soils carry a surface veneer of stones, often

coated with a desert varnish containing at least some al-

lochthonous (foreign) components (Figure 7.1). The stone

veneer often overlies a stone-free subsoil. Dregne (1976,

p. 42) argued that stone mantles were usually the result of

the removal of fines by wind or water, leaving the gravel

as a

lag

deposit. It appears, however, that the stones can be

concentrated at the surface by other means. A mechanism

now widely envisaged is that windblown dusts, settling

on to a desert surface, are washed down between surface

stones, perhaps passing into the regolith along desicca-

tion cracks (see Chapter 19). Weathered rock debris is

thus kept exposed and continually rides to the top of the

accumulating soil materials, being itself too large to be

washed into soil crevices. Thus, far from signifying wind

erosion, desert stone mantles may reflect quite the oppo-

site, a local

accumulation

of significant amounts of mate-

rial; the soils may thus deepen with time in a process that

has been termed 'cumulic pedogensis' (McFadden

et al.

,

1998; Gustavson and Holliday, 1999; Ugolini

et al.

, 2008).

Figure 7.1

Desert pavement capping soils in arid northern

South Australia: (a) pavement of well-sorted stones with sig-

nificant exposure of silts; (b) pavement of poorly sorted stones

resulting in very high areal coverage and little exposed fine

soil material; (c) view across arid desert pavement to residual

hills in the distance. Scattered patches of grass can be seen,

marking locations where the pavement is less complete, and

where water infiltration is possible.