Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

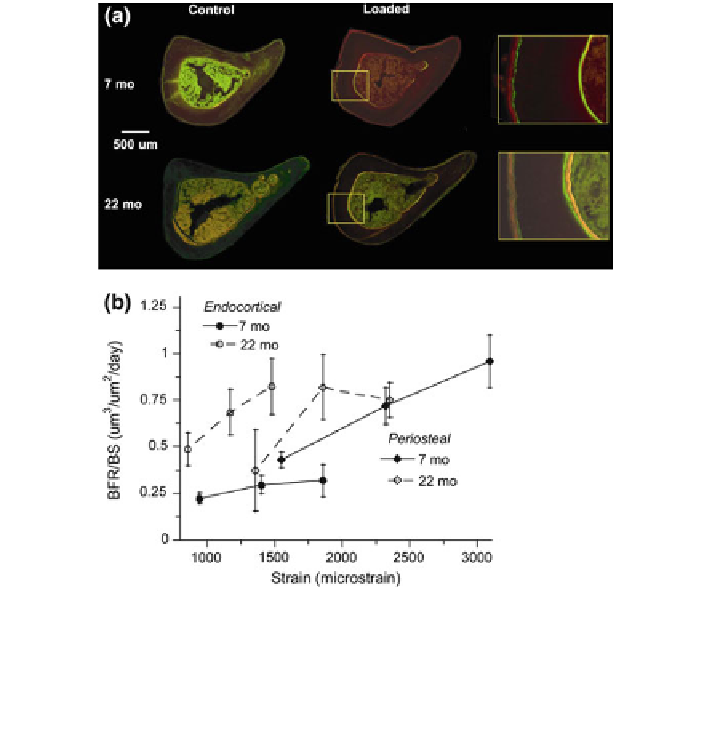

Fig. 2 a Fluorescent photomicrographs of mid-diaphyseal tibial sections from loaded and

control tibias of 22- and 7-months mice. Samples were collected on day 11 following tibial

compression on days 1-5, and fluorochrome labeling on days 5 (green) and 10 (red). An increase

in endocortical and periosteal labeled surface is evident in loaded tibias of both ages compared to

controls. b Bone formation rate measured from tibial sections (n = 8-13 mice/group) from

the same study. There is no loss of mechanoresponsiveness in the old mice. (From Brodt and

Silva [

57

])

that this age was most responsive to loading. Unexpectedly, trabecular bone

volume fraction (BV/TV) was reduced in loaded limbs compared to controls in

4, 7 and 12 month groups, and was unchanged with loading in the 2 month group.

We concluded that, at cortical sites mechanical loading can overcome the normal,

age-related decline in bone formation in mice, with some evidence that the

young-adult skeleton (4 months) is more responsive than the mature to middle-

aged skeleton (7-12 months).

Lynch et al. recently used the axial tibial loading model in two separate studies

to compare bone adaptive responses in young, growing (2 months) versus mature,

adult (6 months) mice [

59

,

60

]. Female C57Bl/6 mice were subjected to 2 weeks

of daily loading (1200 or 2200 le periosteal; 1200 cycles/day, 5 days/week)

and morphology of cortical and trabecular bone was assessed by post hoc

microCT. Comparisons between ages were made challenging because of different

Search WWH ::

Custom Search