Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

Collem-

bolans

Shoots

Root

Feeding

Nematodes

Predaceous

Mites

Mites I

Roots

Mycorrhizae

Nematode

Feeding

Mites

Inorganic

N

Mites II

Saprophytic

Fungi

Predaceous

Nematodes

Fungivorous

Nematodes

Labile

Substrates

Omnivorous

Nematodes

Bacteria

Resistant

Substrates

Flagellates

Amoebae

Bacterio-

phagous

Nematodes

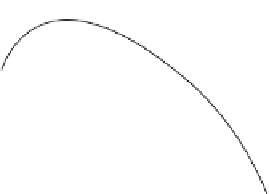

Figure 1.2

Flow diagram of aboveground and belowground detrital inputs in a shortgrass steppe

ecosystem (from Hunt, H.W., D.C. Coleman, E.R. Ingham, R.E. Ingham, E.T. Elliott, J.C. Moore, S.L.

Rose, C.P.P. Reid, and C.R. Morley. 1987. The detrital food web in a shortgrass prairie.

Biology and

Fertility of Soils

3:57-68. With permission from Springer). Note the separation of flows between vari-

ous faunal groups, including the fungivorous Cryptostigmata, collembolans, and nematodes, and

the more generalized feeders, non-cryptostigmatic mites. A majority of the nitrogen mineralization

were calculated to come from the protists, feeding primarily on bacteria, and bacterial and fungal-

feeding nematodes (Ingham et al., 1985).

The complexity presented in

Figure 1.2

c

an be condensed into the dominant pathways

beginning with pools of detritus or SOM that differ in quality. These pools would serve as

the primary energy sources for a suite of bacteria and fungi, each of which is consumed by

a host of microbial consumers and predators. Metabolic wastes and by-products that cycle

back as energy sources and binding agents would be factored in much as C and N are in

the current generation of models. This approach preserves the basic premise of material

transformations that occur in the soil carbon models (Parton et al., 1987; Gijsman et al.,

2002) and material transfers that occur in food web models (Hunt et al., 1987; de Ruiter et

al., 1993) in a way that provides a common currency. A comparison (

Figure 1.3

)

of below-

ground food webs from a wide range of agroecosystems is instructive. The food webs

from Central Plains, Colorado, and Horseshoe Bend, Georgia, in the United States and

two European ones, from Kjettslinge, Sweden, and Lovinkhoeve, the Netherlands, show

varying degrees of aggregation of functional groups, depending in part on the expertise

of the investigators involved. For example, in some webs, flagellates were distinguished

from amoebae, and in others they were aggregated as one: protozoa. Earthworms were not

found at the conventional fields of Lovinkhoeve. With much greater emphasis on above-

ground and belowground interactions currently (see De Deyn and van der Putten, 2005), it

is noteworthy that herbage arthropods were considered only at the Swedish site. For ease

of depiction, material flows to the detrital pool, through the death rates and the excretion

of waste products, were not represented in the diagrams but were taken into account in the

material flow calculations and stability analyses (de Ruiter et al., 1998).

Moore et al. (2003) presented a first approximation of this approach by linking the

activities of organisms within the bacterial and fungal pathways to SOM dynamics and

Search WWH ::

Custom Search