Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

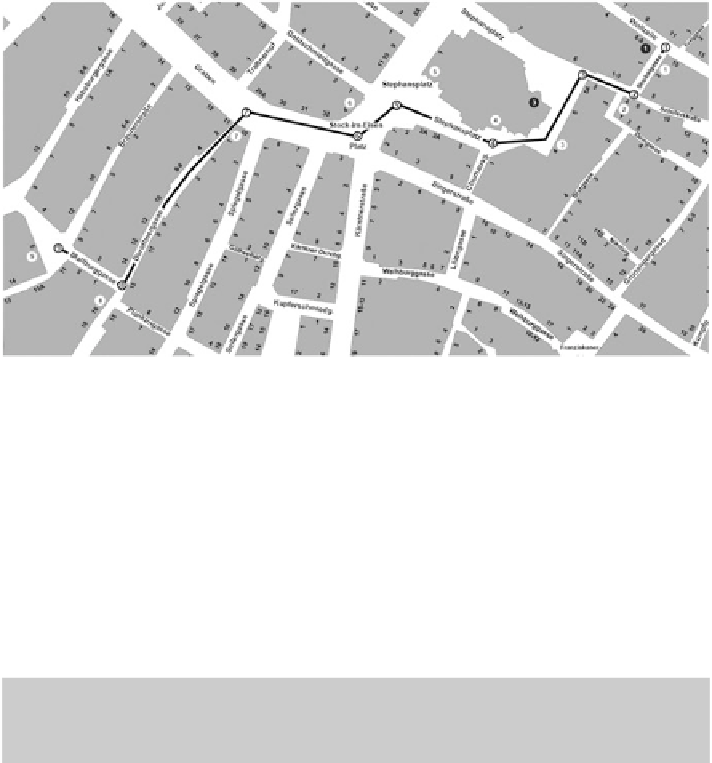

Fig. 5.4

The route investigated in

[

31

]

.

White dots

indicate differing selections between partici-

it turns out that for the given direction of travel, the Bank Austria building has

a higher salience value than the Haas building. Coverage for Bank Austria is

c

D

1, and the orientation is also close to 1, while the Haas building is orientated

nearly completely away from the route. In principle, advance visibility needs to be

calculated for every landmark from every possible direction of approach to cover

for every possible wayfinding situation.

that expands the aspect of structural salience. It accounts for the location of

landmarks along the route and the kind of wayfinding action that needs to

be performed. Since this is route-specific and not a general property of a

Raubal and Winter's formal model has been empirically evaluated by Nothegger,

measures for façade area and shape, color, visibility, and semantic attraction of

a building. Data for one route through Vienna's first district has been collected,

Using this data, for each intersection along the route the most salient landmark

was calculated. These were then compared with the results of a human subject

Search WWH ::

Custom Search