Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

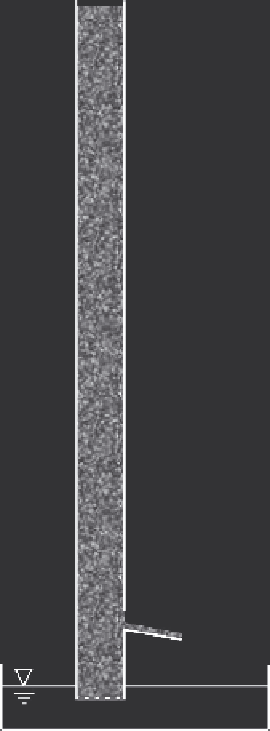

Fig. 14.4 Reconstruction of the experimental set-up described

by Perrault (1674) to measure the movement of water

in a sandy soil. The soil was placed in a lead pipe with

a length of 65 cm and a diameter of 4.5 cm; the

bottom was closed off with permeable cloth. At a

height of about 5.4 cm above the water surface an

opening was made in the pipe to check whether any

water, that had risen into the soil after the bottom had

been inserted in the bath, would be able to flow out in

the manner of a spring.

came out last was not so moist, even though he had twice poured water on the sand of the

top, which came out last. He repeated the experiment with several other types of soil and

set-ups, but the results were similar.

After drawing a number of general conclusions from this experiment, he returns to the

two difficulties, which he raised earlier against the Common Opinion (p. 162).

As regards the first one, which is this penetration, which I don't think can take place, as they believe,

I will say first, that if we are to believe Seneca and Lydiat....theearth does not allow itself to

be penetrated by the rain with such ease as is believed . . . but I add to this reasoning the everyday

experiences one encounters with this penetration of the earth.

He further illustrates this inability of water to penetrate by describing the numerous drainage

problems encountered by farmers and others dealing with soil water management. Following

these general observations in the country side he turns once more to Seneca (p. 166).

The same Seneca asserts that the waters of the rain don't enter into the earth beyond ten feet, which he

vouches for as a good wine-grower, which he says he is, who has often dug into the earth.

This shows again the profound influence Seneca's description of his vineyard experience

(see Seneca, 1971) continued to have even after 17 centuries. Perrault then recounts how