Geoscience Reference

In-Depth Information

seems to have bitterly regretted the loss not only of the ten years in preparing for

and making the expedition but also the ten years of vexation afterwards.

Although by the time the explorers had returned to France in 1744 the issue of the

shape of the Earth was regarded as settled, at least their results were regarded as confir-

mation. Unusually for a campaign organized by the Academy, the principals all pub-

lished individual accounts, presumably because of the breakdown in their relationships

and because of the national differences; it was necessary for the Spanish scientists, for

example, to publish their own independent account to show how their contribution was

of equal status to that of the French. Ulloa's and Juan's account “proved influential in

an unanticipated respect: despite the austerely scientific nature of their enquiries into

geography, geology, hydrography, and climate, they illustrated their work with stun-

ningly beautiful diagrams that incorporated romantic representations of American

landscapes: the first stirrings of what was to be a long story- the nourishing of European

romanticism with images of America” (Fernández-Armesto 2006).

Bouguer's value for the length of the degree of latitude at the equator was 56,768

toises, La Condamine's 56,763 and Juan and Ulloa's 56, 768. Their measurements

confirmed what had become accepted: the Earth was indeed flattened at the poles

and that the Newtonian prediction was correct.

BY THAT TIME the Cassinis had already conceded and agreed that the Earth was a

flattened sphere, the reason being another calculation from the measurement of the

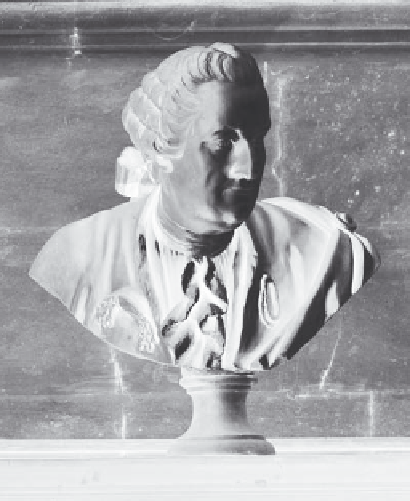

Paris Meridian. Cassini de Thury (Cassini III,

Fig. 26

) went back to basics, deciding

to remeasure Picard's baseline (on which all the surveys depended) and to reduce

Fig. 26

César-François Cassini de Thury (Cassini III). © Observatoire de Paris