Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

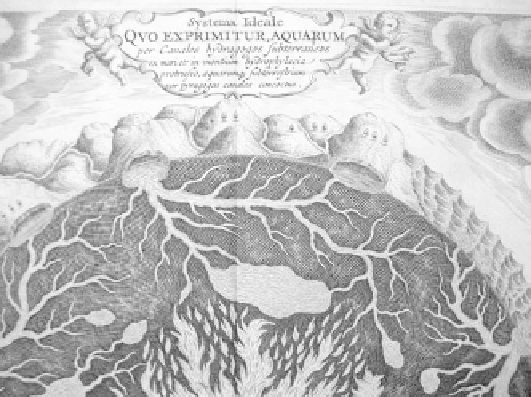

And yet, his ideas did not take hold, and the generally accepted theory

was that of the underground still (Figure 1), where water passed below

ground through channels, was heated by a central fi re and abandoned

its salt, and then condensed in the mountains to feed underground lakes,

which fl owed out at the surface as springs.

Figure 1

The underground still: 17th

century engraving.

1.2.4 The 17th century: the water cycle

Modern geology is being born in the West. A few major works dealing

with subterranean water can be found: “

Mundus subterraneus”

(Athanasius

Kircher, 1665), “

Principia Philosophiae”

(Descartes, 1664), “

Prodromus”

(Stenon, 1669); but they restate the concept of the underground still. It

is in 1674 that Pierre Perrault's “On the Origin of Springs” reveals the

importance of evaporation and infiltration. Perrault proved that the

upper Seine's discharge corresponded to only a sixth of the amount of

water entering the river's watershed. A large percentage of the water had

therefore disappeared. Mariotte (1620-1684) came to the same conclusion,

and during the same period, Halley (1656-1742) quantifi ed evaporation.

The motor bringing water from ocean to mountains and the mechanism

for desalinization were thus discovered at the same time. The modern

conception of the water cycle was, then, born in the 17th century, after

more than two thousand years of debate amongst the greatest scientists

on the planet.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search