Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

products of a burgeoning population of humans with

increasing disposable income (Shrestha et al., 2008). One

outcome of the United Nations Conference on Environment

and Development in 1992 held in Rio de Janeiro was the

ratifi cation of the Convention on Biodiversity. This pro-

moted national and international attention toward the

depletion of biological diversity, a trend that includes

goats. To combat the loss of goat genetic resources world-

wide, many countries have seized opportunities to initiate

in situ and ex situ conservation to preserve the inherent

potential of goats and reduce the endangerment or extinc-

tion of breeds, populations, and landraces.

Goat provides a sizeable proportion of the human diet

in many developing countries. Through owning animals

with multifunctionality, small farmers and the landless

have survived in the face of hunger, poverty, and the

current food crisis (Devendra, 2007). The genetic resources

of goats are not unique to each country but instead are

affi liated intimately with the economic status, social struc-

ture, religious rituals, and most importantly, public policy.

Therefore, preservation of animal genetic resources is nec-

essary to sustain current production levels and to address

future market demands for commodities, trade, fertilizer,

breeding stocks, employment, and recreation. No longer

are goats viewed as pests responsible for soil erosion.

Instead, goats are being viewed in new roles as potential

alleviators of worldwide poverty.

ronment provided by farmers. Wild species undergo physi-

cal changes as they adapt to captivity and are selected for

traits of economic importance. Clutton - Brock (1999)

defi ned a domestic animal as “one that has been bred in

captivity for purposes of economic profi t to a human com-

munity that maintains total control over its breeding, orga-

nization of territory and food supply.” Domestic animals

that revert to their wild state following their escape or

release into an environment favorable for propagation are

known as “ feral ” animals.

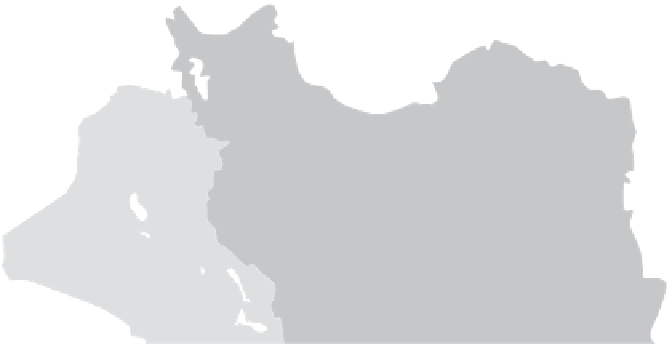

As early as 8500 BC, prehistoric people at the end of

the Mesolithic period raised herds of goats and fl ocks of

sheep in the mountainous areas bordering Iran and Iraq

(Figure 3.1). This conclusion is based on archeological

excavations where goat and sheep bones were uncovered

adjacent to human settlements along with radiocarbon

dating. Archaeological sites in the Kermanshah Valley of

the Zagros Mountains at “Ganj Dareh,” Iran (8000 BC)

and the Euphrates river valley at “Nevali Cori,” Turkey

(9000 BC) are believed to be two separate but distinct sites

where domestication occurred (Vigne et al., 2005). Other

possible sites of domestication include the Indus Basin at

“ Mehrgarh, ” Pakistan (7000 BC), “ Cay ö n ü , ” Turkey

(8500 - 8000 BC), “ Tell Abu Hureyra, ” Syria (8000 - 7400

BC), “ Jericho, ” Palestinian Occupied Territories (7500

BC), and “ Ain Ghazal, ” Jordan (7600 - 7500 BC). The

central Anatolia and the southern Levant also have been

proposed as additional sites of early domestication. New

research has confi rmed that the “ Ganj Dareh ” site contains

the earliest directly dated evidence of livestock domestica-

tion (Zeder and Hesse, 2000 ).

DOMESTICATION

Domestication is an ongoing process that includes both

artifi cial selection and skillful breeding practice in an envi-

ARMENIA

AZERBAIJAN

TURKMENISTAN

TURKEY

CASPIAN

SEA

Tabriz

Daryachech-ye

Urumlyeb

Rasht

Babol

Mashhad

Mosul

-

Tehran

SYRIA

Kirkuk

CYPRUS

Tripoli

Hims

Hamadan

Dash-e-kavir

LEBANON

Malee

Tharthan

Beirut

Kashan

MEDITERRANEAN

SEA

AFGHANISTAN

Damascus

I RAN

Baghdad

IRAQ

Haifa

Esfahan

Karbala

as

Tel Aviv

Amman

Jerusalem

Yazd

An Nasiriyah

Hawral

ISRAEL

JORDAN

Kerman

Figure 3.1

Region where early domestication of goats and sheep occurred.