Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

Overregularization in Adam

Phonology

ed

1.00

Eventual

correct

performance

assumed

(strong

correlation)

0.98

past

tense

0.96

Semantics

0.94

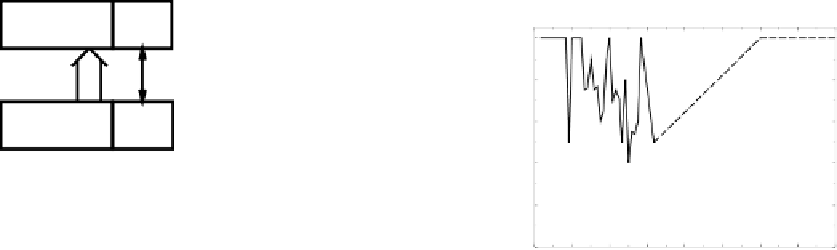

Figure 10.17:

Semantics to phonology mapping, showing

separable inflectional component that maps a semantic repre-

sentation of “past tense” onto the regular phonological inflec-

tion of “add -ed.” The regularity of this mapping produces a

strong correlation between these two features.

0.92

0.90

23456789 0

Years of Age

Figure 10.18:

U-shaped curve of irregular past-tense inflec-

tion production in the child “Adam.” The Y axis shows 1 mi-

nus the overregularization rate, and the X axis his age. In

the beginning, Adam makes no overregularizations, but then,

right around age three, he starts to overregularize at a mod-

est rate for at least 2.5 more years. We must assume that at

some point he ceases to overregularize with any significant

frequency, as represented by the dotted line at the end of the

graph.

were incorporated together with an indirect route via se-

mantics, these low frequency irregulars should come to

depend more on the indirect route than the direct route

represented in this model. This is exactly what was

demonstrated in the PMSP model through the use of

a simulated semantic pathway. For more discussion of

the single versus dual-route debate, see PMSP.

10.5

Overregularization in Past-Tense Inflectional

Mappings

As in the reading model in the previous section,

exceptions to the general rule of “add -ed” exist for

the past tense inflection (e.g., “did” instead of “doed,”

“went” instead of “goed”). Thus, similar issues regard-

ing the processing of the regulars versus the irregulars

come up in this domain. These regular and irregular

past-tense mappings have played an important and con-

troversial role in the development of neural network

models of language.

In this section we explore a model of the mapping

between semantics and phonological output — this is

presumably the mapping used when verbally express-

ing our internal thoughts. For monosyllabic words,

the mapping between the semantic representation of a

word and its phonology is essentially random, except

for those relatively rare cases of onomotopoeia. Thus,

the semantics to phonology pathway might not seem

that interesting to model, were it not for the issue of

inflectional morphology

. As you probably know, you

can change the ending or inflection of a word to convey

different aspects of meaning. For example, if you want

to indicate that an event occurred in the past, you use

the

past tense

inflection (usually adding “-ed”)ofthe

relevant verb (e.g., “baked” instead of “bake”). Thus,

the semantic representation can include a “tense” com-

ponent, which gets mapped onto the appropriate inflec-

tional representation in phonology. This idea is illus-

trated in figure 10.17.

U-Shaped Curve of Overregularization

At the heart of the controversy is a developmental phe-

nomenon known as the

U-shaped curve

of irregular

past-tense inflection due to

overregularization

.InaU-

shaped curve, performance is initially good, then gets

worse

(in the middle of the “U”), and then gets bet-

ter. Many children exhibit a U-shaped curve for produc-

ing the correct inflection for irregular verbs — initially

they correctly produce the irregular inflection (saying

“went,” not “goed”), but then they go through a long

period where they make overregularizations (inflecting

an irregular verb as though it were a regular, “goed”

Search WWH ::

Custom Search