Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

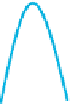

Net pay thickness

Apparent thickness

Figure 10.20

Model data template generated for a turbidite reservoir. Note that the net pay lines are effectively averages as there is

considerable overlap. Blue wells were blind tests whilst the red well was the basis for the pseudo-well data in the model. After Fervari and

Luoni (

2006

).

surveys effectively highlight where production effects

have occurred (

Fig. 10.23

). Amplitude maps can give

a dramatic indication of large scale changes over the

field area (

Fig. 10.24

). Detailed interpretation of the

time-lapse signal in terms of fluid flow (e.g. identify-

ing barriers and estimating sweep efficiency in reser-

voir compartments) and the identification of

remaining reserves requires careful reference to the

baseline reservoir description and geological model.

The results can be used to optimise infill drilling and

manage injection/production strategies. The reader

is referred to excellent summaries of time-lapse tech-

nology given by Jack (

1997

), Calvert (

2005

)and

Johnston (

2013

).

Figure 10.25

shows a view of the time-lapse pro-

cess in which a seismic floodmap based on time-lapse

seismic interpretation is used to update the field

simulation. In some instances, the level of integration

is even greater than that implied in the figure, with

the reservoir simulation being fully integrated with

the seismic observations via a

dynamic and static reservoir models have a high

degree of consistency. Many modern time-lapse pro-

jects seek to

(Gutteridge et al.,

1994

)

by comparing seismic models generated from the

simulation with the acquired data. In this way history

matching of the simulation can be validated or

adjusted. rock physics modelling (

Chapters 5

and

8

)

provides the basis for interdisciplinary consistency

(e.g. Gawith and Gutteridge,

2007

).

Time-lapse seismic is a relatively new technology

founded largely through advances in the understand-

ing of reservoir rock physics in the late 1980s and

early 1990s (e.g. Wang,

1997a

). Prior to this time,

time-lapse effects had generally been described from

fields on land with fairly large changes in compress-

ibility, a classic example being the fire flood project

described by Greaves and Fulp (

1987

). It was uncer-

tain whether or not there was sufficient signal or

detection capability to make it a key technology for

offshore developments particularly in conventional

oil reservoirs. From tentative beginnings, various

studies, largely on North Sea fields, essentially proved

technical viability. Subsequently, experience shows

that the net value gain associated with the use of

'

close-the-loop

'

'

(Riddiford and Goupillot,

1993

). A good example of

this level of discipline integration has been described

from Draugen field (Guderian et al.,

2003

), where

'

shared earth model

237