Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

Some early history

The Manchester Baby and the Cambridge EDSAC computers

In his draft report on the design for the EDVAC, von Neumann analyzed the technical options for

implementing the memory of the machine at length and concluded that the ability to construct large mem-

ories was likely to be a critical limiting factor. The first “stored program”

computer to actually run a program was the University of Manchester's

“Baby” computer. This was a cut-down design of their more ambitious

“Mark 1” and was built primarily to test the idea of hardware architect,

Freddie Williams, to use a cathode ray tube - like the screens of early

televisions - as a device for computer memory. In June 1948, the Baby ran

a program written by co-architect Tom Kilburn to find the highest factor

of 2

18

(

Fig. 2.22

). The program was just a sequence of binary numbers

that formed the instructions for the computer to execute. The output

appeared on the cathode ray tube and, as Williams recounted, it took

some time to make the system work:

When first built, a program was laboriously inserted and the start switch

pressed. Immediately the spot on the display tube entered a mad dance. In

early trials it was a dance of death leading to no useful result and, what was

even worse, without yielding any clue as to what was wrong. But one day it

stopped and there, shining brightly in the expected place, was the expected

answer.

9

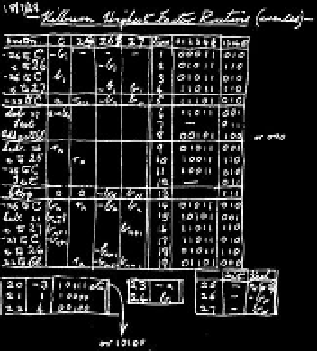

Fig. 2.22. Kilburn's highest factor rou-

tine from July 1948. The program ran for

fifty-two minutes, and executed about

2.1 million instructions and made more

than 3.5 million memory accesses.

The success of the Manchester Baby experiment led to the construction

of the full-scale Manchester Mark 1 machine. This became the prototype

for the Ferranti Mark I, the world's first “commercially available general-

purpose computer”

10

in February 1951, just a month before Eckert and

Mauchly delivered their first UNIVAC computer in the United States.

While the Manchester Baby showed that a stored program com-

puter was feasible, it was the EDSAC, built by Maurice Wilkes (

B.2.6

) and

his team in Cambridge that was really the “first complete and fully opera-

tional regular electronic digital stored-program computer.”

11

The computer

used mercury delay-lines for storage as reflected in Wilkes's choice of the

name EDSAC - Electronic Delay-Storage Automatic Calculator. The devel-

opment of a suitable computer memory technology was one of the major

problems for the early computer designers. It was mainly because of stor-

age difficulties that EDVAC-inspired computers in the United States were

delayed and lagged behind the Manchester and Cambridge developments.

Wilkes chose to use mercury delay-lines for EDSAC because he knew that

such delay-lines had played an important role in the development of radar

systems during the war. Wilkes had a working prototype by February 1947,

just six months after he had attended the Moore School Lectures. Working

with a very limited budget had forced Wilkes to make some compromises

in the design: “There was to be no attempt to fully exploit the technology.

Provided it would run and do programs that was enough.”

12

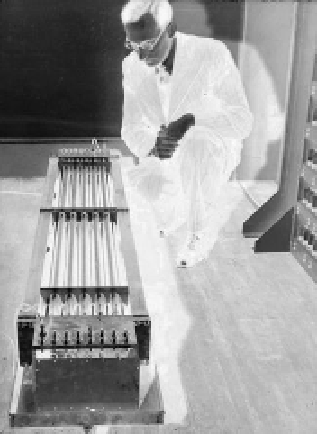

B.2.6. Maurice Wilkes (1913-2010) seen

here checking a mercury delay-line

memory. He was a major figure in the

history of British computing and at the

University of Cambridge he led the team

that designed and built the first fully

operational stored-program computer.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search