Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

Code breakers and bread makers

No history of the early days of computing would be complete

without recounting the pioneering work of the British cryptologists at

Bletchley Park and the development of the first computer dedicated to

business use.

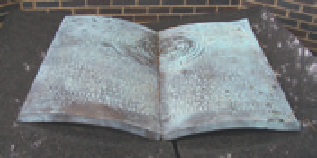

Fig. 1.19 Memorial to Polish code breakers

at Bletchley Park. Their contribution was

critical to the development of the Bombe

machines used to break the Enigma codes.

Bletchley Park, Enigma, and Colossus

During World War II, British mathematicians and scientists had

been looking to automated machines for their top-secret work on code

breaking at Bletchley Park. Both Turing and his Cambridge mentor Max

Newman (

B.1.7

) were intimately involved in designing and building auto-

mated machines to assist in decrypting secret German military com-

munications. Turing was involved in deciphering messages encrypted

using the famous Enigma machine. With a head start given to them by

Polish Intelligence (

Fig. 1.19

), Turing helped develop electromechanical

machines, known as

bombes

, which were used to determine the settings of

the Enigma machine. These machines were operational as early as 1940

and contributed greatly to protecting convoys from U-boats in the North

Atlantic.

The German High Command

in Berlin used an even more com-

plex cipher machine called Lorenz.

Newman's team built a machine -

called Heath Robinson after a pop-

ular cartoonist who drew eccentric

machines - that showed it was possible to make a device to break

the Lorenz codes. This was followed by the ULTRA project to build an

all-electronic version of Heath Robinson called Colossus (

Fig. 1.20

).

Although this machine was certainly not a general-purpose computer,

it had 1,500 vacuum tubes as well as tape readers with optical sensors

capable of processing five thousand teleprinter characters a second. The

machine was designed and built by Tommy Flowers (

B.1.8

), an engineer

at the U.K. Post Office's Dollis Hill research laboratory in London, and

became operational in December 1943, more than two years before the

ENIAC. One of the great achievements of Colossus was reassuring the

Allied generals, Eisenhower and Montgomery, that Hitler had believed

the deception that the D-Day invasion fleet would come from Dover.

The immense contribution of code breakers was recognized by Winston

Churchill when he talked about “the Geese that laid the golden eggs but

never cackled.”

17

Fig. 1.20 A photograph of the Colossus

computer, the code-breaking machine

that nobody knew existed until many

years after the war. It was designed and

built by Tommy Flowers, an engineer at

the British Post Office in 1943.

B.1.7 Max Newman (1897-1984) was a

brilliant Cambridge, U.K., mathemati-

cian and code breaker. It was Newman's

lectures in Cambridge that inspired

Alan Turing to invent his famous Turing

Machine. Newman was at Bletchley Park

during World War II and his team was

working on the messages encrypted by

the Lorenz cipher machine. They built

a machine - called Heath Robinson - to

break the Lorenz code, and this was later

automated as the Colossus computer.

The main task for the code breakers was to read the text from a paper

tape and to work out the possible settings of the twelve rotors of the

encrypting device. Colossus was first demonstrated in December 1943

Search WWH ::

Custom Search