Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

captured many of the principles to be found in today's computers. In

particular, Babbage's design separated the section of the machine

where the various arithmetical operations were performed from the

area where all the numbers were kept before and after processing.

Babbage named these two areas of his engine using terms borrowed

from the textile industry: the

mill

for the calculations, which would

now be called the central processing unit or CPU, and the

store

for

storing the data, which would now be called computer memory. This

separation of concerns was a fundamental feature of von Neumann's

famous report that first laid out the principles of modern computer

organization.

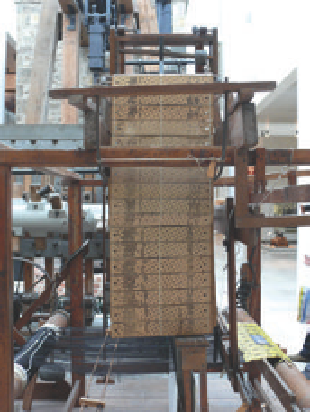

Another key innovation of Babbage's design was that the instruc-

tions for the machine - or program as we would now call them - were

to be supplied on punched cards. Babbage got the idea of using punched

cards to instruct the computer from an automatic loom (

Fig. 1.18

)

invented in France by Joseph-Marie Jacquard (

B.1.5

). The cards were

strung together to form a kind of tape and then read as they moved

through a mechanical device that could sense the pattern of holes on

the cards. These looms could produce amazingly complex images and

patterns. At his famous evening dinner parties in London, Babbage

used to show off a very intricate silk portrait of Jacquard that had been

produced by a program of about ten thousand cards.

Babbage produced more than six thousand pages of notes on his

design for the Analytical Engine as well as several hundred engineering

drawings and charts indicating precisely how the machine was to oper-

ate. However, he did not publish any scientific papers on the machine

and the public only learned about his new ambitious vision through a

presentation that Babbage gave in 1840 to Italian scientists in Turin.

The report of the meeting was written up by a remarkable young engi-

neer called Luigi Menabrea - who later went on to become a general in

the Italian army and then prime minister of Italy.

Fig. 1.18 A photograph of Jacquard's

Loom showing the punched cards encod-

ing the instructions for producing intri-

cate patterns. The program is a sequence

of cards with holes in carefully specified

positions. The order of the cards and the

positions of these holes determine when

the needles should be lifted or lowered

to produce the desired pattern.

Ada Lovelace

B.1.5 Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752-

1834) (left) and Philippe de la Salle

(1723-1804) pictured on a mural in

Lyon (Mur des Lyonnais). Philippe de

la Salle was a celebrated designer, who

made his name in the silk industry.

Jacquard's use of punched cards to pro-

vide the instructions for his automated

loom inspired Babbage, who proposed

using punched cards to program his

Analytical Engine.

It is at this point in the story that we meet Augusta Ada, Countess

of Lovelace (

B.1.6

), the only legitimate daughter of the Romantic poet,

Lord Byron. Lovelace first met Babbage at one of his popular evening

entertainments in 1833 when she was seventeen. Less than two weeks

later, she and her mother were given a personal demonstration of his

small prototype version of his computing engine. Unusually for women

of the time, at the insistence of her father, Ada had had some mathe-

matical training. After this first meeting with Babbage, Ada got mar-

ried and had children but in 1839 she wrote to Babbage asking him

to recommend a mathematics tutor for her. Babbage recommended

Search WWH ::

Custom Search