Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

travels down the axon and is passed on to the dendrites of neighboring neurons

through the synapses (see

Fig. 13.15

). A typical neuron operates on a “thresh-

old” or “all-or-none” principle meaning that the input stimulation, represented

by the sum of all the incoming signals, must be above a certain threshold for

the cell to produce an output signal.

The cerebral cortex consists of up to six horizontal layers of neurons and

is about 2.5 millimeters or one-tenth of an inch thick. The neurons in each of

these layers connect vertically to neurons in adjacent layers. With these new

discoveries about the brain in the first half of the twentieth century, Nobel

Prize recipient Charles Sherrington poetically imagined how the workings of

the brain would look as it woke up from sleep:

(a)

(b)

The great topmost sheet of the mass, that where hardly a light had twinkled

or moved, becomes now a sparkling field of rhythmic flashing points with

trains of traveling sparks hurrying hither and thither. The brain is waking

and with it the mind is returning. It is as if the Milky Way entered upon

some cosmic dance. Swiftly the head mass becomes an enchanted loom

where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a

meaningful pattern though never an abiding one; a shifting harmony of

subpatterns.

20

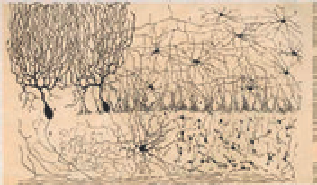

Fig. 13.14. Santiago Ramón y Cajal's

drawing of: (a) a Golgi-stained cortex of

a six-week-old human infant and (b) cells

of the chick cerebellum.

As we have seen, Wiener, von Neumann, Turing, and other early computer pio-

neers were fascinated with the possibility of computers performing operations

that would normally be classified as requiring intelligence. Warren McCulloch

and Walter Pitts had produced a simple mathematical model of a neuron that

only “fired” when the combination of its input signal exceeded a certain thresh-

old value (see

Fig. 13.16

). In their famous 1943 paper “A Logical Calculus of

the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity,” they showed that a network of such

neurons could carry out logical functions. They also suggested that, much like

a human brain, these artificial neural networks (ANNs) could learn by forming

new connections and by modifying the neural thresholds. Alan Turing put for-

ward similar ideas in an unpublished paper on “Intelligent Machinery” in 1948.

Turing suggested, “The cortex of an infant is an unorganised machine, which

can be organised by suitable interfering training.”

21

The basis of modern ANNs is a mathematical model of the neuron called

the

perceptron

introduced by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957. In the original model

Fig. 13.15. Sketch of a biological neural

network showing dendrites, axons, and

synapses.

Dendrite

Axon Te rminal

Node of

Ranvier

Cell body

Schwann cell

Axon

Myelin sheath

Nucleus

Search WWH ::

Custom Search