Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

world computer chess championship in 1980. The U.S. Department of State

temporarily confiscated Belle in 1982 as it was heading to the Soviet Union to

participate in a computer chess tournament. The State Department claimed it

was a violation of U.S. technology transfer law to ship a high-technology com-

puter to a foreign country. The next prize of $10,000 for the first program to

achieve an Elo rating of 2500 was awarded to a computer called Deep Thought

in August 1989. Deep Thought was a computer specifically designed to play

chess by Feng-hsiung Hsu and his fellow graduate student Murray Campbell at

Carnegie Mellon University. IBM then recruited Hsu and Campbell to develop a

successor to Deep Thought. The result was Deep Blue, a parallel computer with

thirty processors, enhanced by 480 special-purpose chess chips (

Fig. 13.11

).

Deep Blue was capable of evaluating two hundred million positions a second

and could typically search six to eight moves ahead, and sometimes more. A

team of three chess grand masters provided its opening library, and its end-

game database included many six-piece endgames as well as those with five

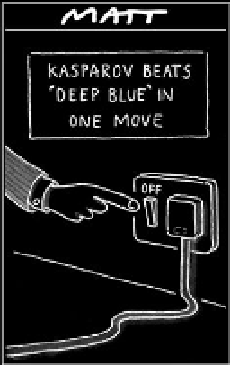

pieces and fewer. In May 1997, world champion Garry Kasparov took on Deep

Blue in a six-game match held in New York (

Fig. 13.12

). The computer won a

close match with two wins for Deep Blue, one for Kasparov, and three draws.

The $100,000 Fredkin Prize went to Feng-hsiung Hsu, Murray Campbell, and

Joseph Hone from IBM. After the match, Kasparov wrote:

Fig. 13.11. IBM's Deep Blue chess com-

puter first played Kasparov in 1996.

On that occasion the world champion

managed to beat the machine. Kasparov

famously lost the rematch a year later.

The decisive game of the match was Game 2, which left a scar in my

memory … we saw something that went well beyond our wildest expectations

of how well a computer would be able to foresee the long-term positional

consequences of its decisions. The machine refused to move to a position that

had a decisive short-term advantage - showing a very human sense of danger.

16

Neural networks

In the audience for Norbert Weiner's neurophysiology talk in 1942 was

Warren McCulloch (

B.13.8

), a professor of psychiatry in Chicago. With a pre-

cocious eighteen-year-old mathematician called Walter Pitts, McCulloch devel-

oped the first model of the brain as an electrical network of interconnected

neurons. They argued that their idealized “neural network” model captured

the key features of the brain's physiology. Von Neumann was so impressed by

this work that, together with Wiener and Howard Aiken from Harvard, he orga-

nized a small workshop at Princeton in January 1945 at which McCulloch and

Pitts were invited to present their neural network model. Ideas from neural

networks were fresh in von Neumann's mind when he wrote his “Draft Report

on the EDVAC” later that year - in which he referred to the basic functional

units of the computer as “organs” and made comparisons of the functions of

these units with the biological functions of neurons.

The importance of the brain in determining human emotions was rec-

ognized by Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine,” as long ago as 400

B.C.

He

said, “Men ought to know that from nothing else but the brain come joys,

delights, laughter and sports, and sorrows, griefs, despondency, and lamenta-

tions.”

17

The human brain has a similar structure to brains of other mammals

but is significantly larger in relation to body size compared to most animals. The

relative increase in size of the human brain is mainly due to the greater size of

Fig. 13.12. The newspapers and other

media portrayed the 1997 match

between World Chess Champion Garry

Kasparov and IBM's Deep Blue computer

as a battle between human and machine.

The cover of

Newsweek

proclaimed it “The

Brain's Last Stand.”

Search WWH ::

Custom Search