Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

ARPA program set the precedent for providing the research base at four

of the first universities to establish graduate programs in computer sci-

ence: U.C. Berkeley, CMU, MIT, and Stanford. These programs, started in

1965, have remained the country's strongest and have served as role mod-

els for other departments that followed. Their success would have been

impossible without the foundation put in place by Lick in 1962-64.

29

Doug Engelbart and the mouse

Fig. 8.19. Doug Engelbart's mouse from

1967. This prototype mouse, invented

by Engelbart at the Stanford Research

Institute, rolled on two sharp wheels fac-

ing 90 degrees from each other.

On Engelbart's return home from military service in World War II,

he had been inspired by reading Vannevar Bush's visionary essay “As We

May Think,” published in 1945. Bush accurately foresaw the days when

scientists would be drowning in information:

Publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make

real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being

expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading

through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the

same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

30

Bush envisioned a machine he called the “memex”: “a device in which

an individual stores all his topics, records, and communications, and

which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed

and flexibility.”31

31

In 1957, when Engelbart joined the Stanford Research

Institute (SRI), he was finally able to start realizing his dream of creating

a memex with funding initially from Bob Taylor, then at NASA, and later

from Licklider at ARPA. (See

Chapter 10

,

B.10.10

for a brief biography of

Taylor.)

Engelbart and his team are best known for their invention of the

mouse (

Fig. 8.19

), but they also pioneered many other features of the pres-

ent-day GUI, in which the user controls a cursor on the screen to select

options from menus, start programs by clicking icons, and perform other

operations. Engelbart was not sure why it was called a mouse: “None of

us would have thought that the name would have stayed with it out into

the world, but the thing that none of us would have believed either was

how long it would take for it to find its way out there.”

32

Engelbart's researcher, Bill English, created the first mouse out of a

hollowed-out block of wood with two small wheels that allowed the user

to control the movement of a cursor on the computer screen (

Fig. 8.20

). At

an event that has been called the “Mother of All Demos” at a major computing conference in San Francisco

in December 1968, Engelbart demonstrated his group's “electronic office” software, called NLS (short for oN

Line System), in which he introduced the mouse, video conferencing, word processing, a real-time editor, and

split-screen displays to the world. He also demonstrated a prototype of Bush's memex idea by showing how

the user could select a single word in a text document and be instantly linked to a second document. This

prototype was the first implementation of a

hypertext

system, which enables the user to jump from one docu-

ment to another, such as we now use daily on the World Wide Web. Butler Lampson and Peter Deutsch, both

early recruits to Xerox PARC, had worked part-time for Engelbart in the 1960s and were both influenced by

the vision of the NLS electronic office software and by the 1968 demo.

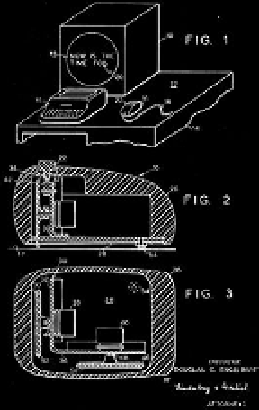

Fig. 8.20. Engelbart's “mouse patent”

drawings. The word

mouse

does not

appear in Engelbart's patent for the com-

puter pointing device. The knife-edged

wheels each rolled in just one direction,

transmitting movement information for

that direction. Each slid without turning

when the mouse was moved in the other

direction.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search