Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

cent were women. In addition, 460,000 children

died (representing 20 per cent of all deaths).

Unlike many things that we think of as

diseases,

AIDS is not characterised by a set of unique

clinical features common to each patient. It is a

syndrome

—a set of symptoms. The particular set

of symptoms varies from one part of the world

to another. For some regions, there is a

clinical

case definition

that provides a checklist of

symptoms, allowing clinicians to diagnose the

disease.

HIV destroys the ability of the human body to

resist infection. The resulting decline in the

immune system allows certain (often locally

specific) opportunistic bacterial, fungal, protozoal

or viral infections to flourish. It may also allow

the development of some kinds of cancerous

tumour.

The virus is passed between people in blood,

semen and vaginal secretions. Thus it may be

transmitted through infected blood transfusions,

injection syringes, sexual intercourse and between

mother and child at the time of birth. Worldwide,

the main mode of transmission is through sexual

intercourse and to a much lesser, but significant

extent, between infected mothers and their

newborn babies. Other major channels of

transmission are transfusions of unscreened blood

and use of blood products derived from

unscreened sources and use of infected equipment

for injections, including the use of various types

of recreational drugs. The rate of sexual

transmission is increased if people have active

sexually transmitted diseases that result in open

wounds on the genitals.

AIDS affects people in all walks of life.

Unlike leprosy, smallpox or measles, those who

are infected do not show any externally visible

signs. In addition, the disease has a very long

'latency period' during which a person shows

little or no sign of ill-health, can be normally

active, but is also able to pass the infection to

other people. This period ranges from a few

months up to fifteen or even twenty years. A

person may not know that they are infected and

thus may infect many others. For this reason,

whatever number of people with symptoms

appear to the medical services of a country and

are diagnosed as having AIDS, there will most

probably be a greater number who are HIV-

positive. Indeed, the numbers of people who are

diagnosed as having AIDS and being HIV-

positive will depend on the quality and form of

surveillance that exists. This is cost and

administration-dependent, and under-recording

of both is likely to increase with national

poverty, and

vice versa

.

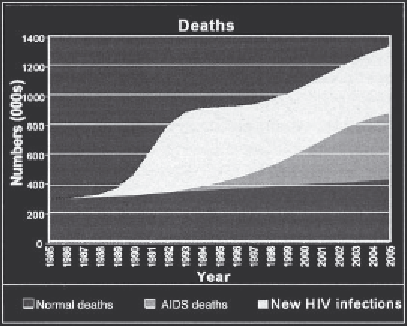

Figure 39.1 shows a projection for an African

country of the relationship between 'normal'

deaths, AIDS deaths and numbers of people in the

population who are HIV-positive and who will

therefore become ill and die within a limited

period.

AIDS AND HIV DISTINGUISHED

In looking at Figure 39.1, we must be careful not

to confuse statements about seroprevalence (the

numbers of people in a population who are HIV-

positive—usually expressed as a percentage of the

population) and statements about the numbers of

people who are actually ill with the disease (usually

expressed as the number per 100,000 of a national

population). It is important to make a clear

distinction between someone being 'HIV-positive'

Figure 39.1

Projected normal deaths, AIDS deaths and

future HIV infections in an African country, 1985-2005.