Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

authorities, they may remain illegal on account of

their non-observance of legislated labour

arrangements. Indeed, with reference to 1989

figures, Roberts (1994: p. 16) notes that up to

three-quarters of workers in Mexican micro-

enterprises are not covered by social security. In

Latin America more generally, it is estimated that

only 2 to 5 per cent of self-employed persons (the

largest group of the informally employed in the

continent) have access to social security, mainly

due to high costs, administrative difficulties, lack

of incentives due to the eroding value of pensions,

and uncertainty in occupational prospects

(Tokman 1991: pp. 152-3; see also Lloyd-Sherlock

1997).

Lest it be thought that lack of social security

applies only to informal economic operations, it is

important to bear in mind that formal sector firms

may engage in similar practices. In Mexico in

1989, for example, formal sector employers were

not paying social security contributions for up to

17 per cent of their workforce (Roberts 1994: p.

16). This is also found in the Philippines, where

many multinational and indigenous factories use

loopholes in the law to avoid commitments to

social security, fringe benefits and redundancy

packages. This often takes the form of hiring

workers on a temporary basis (usually up to three

months), letting them go when their contracts

expire but re-employing them at a later date. This

fulfils the twin imperative of capitalising on

workers' previous training but denying them the

continuous service required for the status of

permanent employee and its attendant privileges

(Chant and McIlwaine 1995: Chapter 4). In many

countries, the pressure exerted by international

financial institutions to reduce 'structural

rigidities' in the workforce and to encourage

greater labour 'flexibility' has led to the passing of

labour law revisions to facilitate these processes

(Green 1996: pp. 109-10;Tironi and Lagos 1991).

In Peru, for example, legislation was introduced in

1991 that gave rights to employers to hire people

on 'probationary' contracts with minimal

entitlement to fringe benefits and no

compensation payable on their release (Thomas

1996: p. 91). In Bolivia, the new economic policy

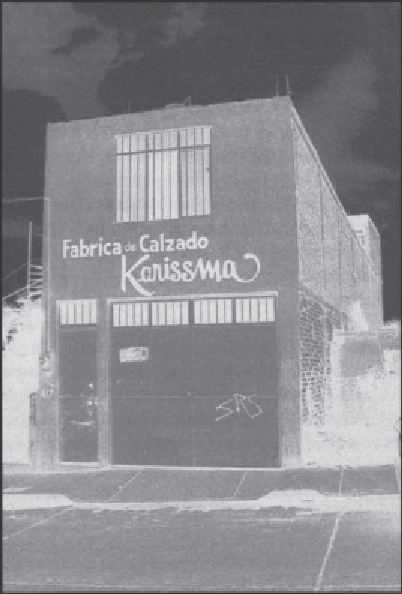

Plate 38.2

Small-scale shoe factory in a residential

neighbourhood, León, Mexico

(photograph: Sylvia

Chant)

.

Tokman (1991: p. 143) identifies three types of

legality pertinent to the demarcation between

formal and informal sector enterprises.

1

Legal recognition as a business activity (which

involves registration, and possible subjection

to health and security inspections).

2

Legality in respect of payment of taxes.

3

Legality

vis-à-vis

labour matters such as

compliance with official guidelines on

working hours, social security contributions

and fringe benefits.

In many cases, informal businesses or operators

may be legal in some ways but not in others. Social

security is often the most costly aspect of legality,

so while micro-enterprises are often registered as

businesses with the relevant local or national