Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

ability of the centre to attract continuing

investment, not only to maintain the fabric, but

also to allow for improvement and adaptation to

changing needs' (URBED and Comedia 1994).

The British government has since issued a list of

indicators of vitality and viability, which local

planning authorities and other town centre

interests are expected to use in assessing the

possible impacts of retail development

(Department of the Environment 1996: Figure 2).

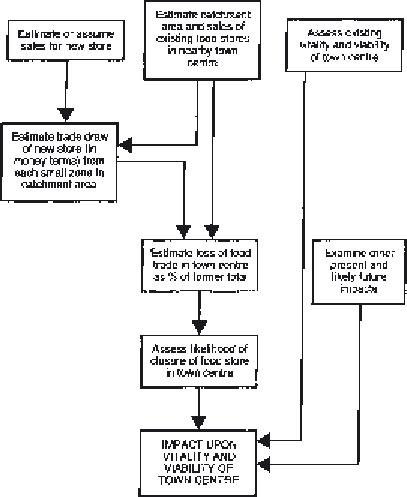

The method described in Figure 33.7 is typical

of those used by planning consultants in the UK

to investigate the probable impacts of proposed

new retail facilities. For the sake of simplicity, the

example taken is of a proposed large food store.

The ultimate aim of the exercise is to predict the

extent to which the proposed development will

affect the vitality and viability of a nearby

established town centre. Impacts upon other

modern large food stores in the local area can also

be assessed, but these are not usually held to be

significant for planning purposes. The method

clearly builds upon the principles of market area

analysis already discussed. This leads to a prediction

of trading impact: that the town centre will lose

x

per cent of its retail trade, for example. There is

then a further stage of assessing impacts upon

vitality and viability. This requires the exercise of

informed judgement rather than simple

application of some technical procedure.

This type of impact assessment clearly makes

use of geographical skills applied to a policy-

making environment. Ultimately, however, the

assessment is incomplete: it concentrates mainly

on economic impact and to a limited extent on

environmental impact. UK planning policy and

practice pay little attention to the social impact

of retail change, as one might expect in a

situation where the distributional effects of social

and economic change generally have no official

place in planning law and procedures. However,

this is an area where geographical research could

make a substantial impact. This theme is

developed further in the concluding section to

this chapter.

Another area of research that needs to be

applied more rigorously is the investigation of

retail impacts

after

the store or centre in question

has opened. The very extensive literature review

carried out by BDP Planning (1992) for the

Department of the Environment was able to

identify only a few competent and thorough

studies of retail impacts. More recently, the impacts

of regional shopping centres such as the Metro

Centre in Gateshead, Merry Hill in the West

Midlands and Meadowhall in Sheffield have been

investigated (Howard 1993; Howard and Davies

1993; Tym 1993; see Box 33.2). A study of long-

term changes in grocery store location and size in

Cardiff (Guy 1996b) suggested that trading impact

is difficult to identify in isolation from the many

other causes of retail growth and decline. In this

particular case, the development of a few large new

food stores coincided with the closure of several

smaller supermarkets and independently owned

food shops, but precise cause-and-effect sequences

were hard to detect. Changes in the spatial

provision of food shopping were better described

as the outcome of a general process of

Figure 33.7

Methodology for assessing the impacts of a

new large food store on town centre vitality and viability.