Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

notion of journey-to-crime, showing the strong

distance decay effects linking offender residence

and the place of the crime, but a more fruitful

framework has been developed by Paul and

Patricia Brantingham in their work on the

geometry of crime (Brantingham and

Brantingham 1981). This suggested that crime

would be concentrated where the offender's

perception of opportunity (awareness space)

overlapped with actual opportunities in the

environment. Offenders' perceptions are skewed

towards areas in which most of their normal

legitimate activity takes place—home, school,

work and leisure.

In the last decade, the dualism of offence and

offender has been reaffirmed, although the slant

has been less towards theoretical understanding of

offender behaviour and more towards its

pragmatic utility for crime prevention and

policing. Developments in offender profiling

explicitly aimed at managing risk, rather than pure

rehabilitation, are beginning to show their

potential. This is not just about psychology but

about all aspects of the predictability of serial

offending. Geographical profiling is one element

in the crime analyst's toolkit, aided by mapping

technologies provided by geographical

information systems (GIS) to display patterns of

offending, known associates and

modus operandi

against demographic, land-use or other

information relevant to the distribution of

potential targets. Equally, these techniques are used

to identify hot spots of crime —clusters of

offences in particular locations (Hirschfield

et al.

1996; Sherman 1995) —using the power of

modern computers to provide regular updates that

highlight patterns as they happen rather than after

the event.

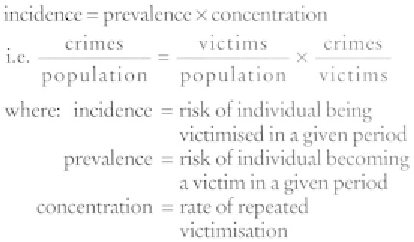

victims, who previously had been the forgotten

item. Much of this knowledge relates to the risk

of victimisation, where it is important to recognise

the distinctions summed up by the simple

equation:

So a high rate of victimisation can mean a few

people repeatedly victimised (for example,

domestic violence) or many people rarely

victimised more than once (e.g. pickpocketing).

The role of repeat victimisation has only recently

been fully recognised. It applies to all the high-

volume categories of crime—in 1995, 19 per cent

of burglary victims suffered two or more

victimisations, 28 per cent of car crime victims,

and 37 per cent of contact crime victims

(wounding, assault, mugging, snatch theft). We

know that there is diffusion of repeat victimisation

across crime types (being a victim of violence

increases your risk of burglary, and

vice versa

), but

as yet little is known about the geography of

repeats.

The various sweeps of the British Crime

Survey show a persistent association of the

incidence of victimisation with certain types of

neighbourhood. High risks tend to be associated

with the poorest council estates, mixed inner

metropolitan areas and high status non-family

areas. Conversely, the lowest risks are associated

with agricultural and retirement areas, modern

high-income family housing, and affluent

suburban areas. However, these are very much

generalisations subject to considerable variation

between types of victimisation. Area risks interact

with other risks (demography, lifestyle and status)

to produce complex patterns, for example the

Victims

Victims are the crucial element in the criminal

process. Numerically, they make the bulk of

decisions about crime, without which no incident

would enter the criminal justice system. The

introduction of victim surveys over the last twenty

years means that we now know more about