Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

directly accessible at the surface some-

where because of tectonic movements.

There is a great difference between

oceanic and continental crust;

oceanic

crust

is composed almost entirely of

the volcanic rock basalt, whereas con-

tinental rocks are extremely varied in

composition, including the whole range

of igneous rocks together with all the

different types of rock derived from

them. However, the average composi-

tion has been estimated to be similar

to a mixture of granite and basalt.

The present-day coastlines are arbi-

trary, in the sense that sea level fluctu-

ates through time in response to various

geological processes. The formation or

removal of ice sheets and the uplift or

depression of land masses cause either

the retreat or advance of the shorelines

across the continental margins. The

true margin of the continents may be

taken as a line about halfway down the

continental slope, where the nature

of the underlying crust changes from

continental type to oceanic type (Figure

2.5). Measured in this way, the 'conti-

nents' would occupy around 40% of the

Earth's surface area rather than less than

the 30% that currently consists of land.

Looking in more detail at the Earth's

surface, it becomes apparent that a large

proportion of it consists of either plains

or plateaux on land, or the deep-ocean

floor; these show little variation in relief

until interrupted by the extreme eleva-

tions and depressions of the mountain

ranges and deep sea trenches, which

occupy only about 3% of the surface

area. Between these two dominant

levels is a region of intermediate depths,

amounting to perhaps 15% of the total

area, representing the continental

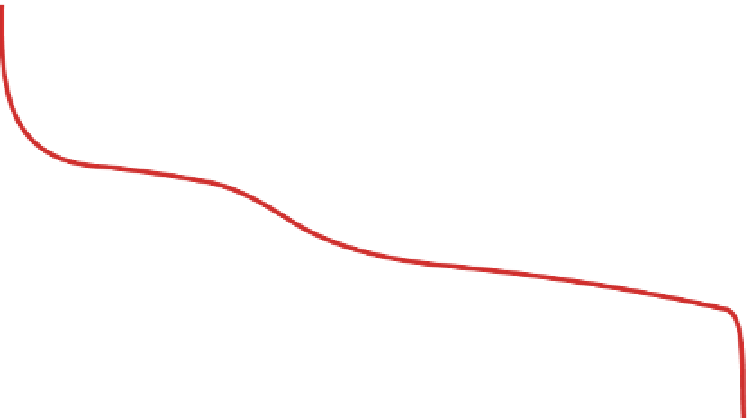

slopes and the ocean ridges. The reason

10

highest mountain

2

continent

ocean

5

average

height

6

7

ocean ridge and

continental slope

sea level

0

km

average depth

-5

continental crust

oceanic crust

-10

deepest ocean

20

40

60

80

100

% surface area

Figure 2.5

The hypsographic curve. This graphical representation shows the variation in surface

height (and depth) in terms of the proportion of surface area occupied; there are two large parts of

the graph corresponding respectively to continental plains and deep ocean, with a transitional part

representing the continental slopes and ocean ridges; areas of extreme relief (mountain ranges and

ocean trenches) occupy a very small part of the total.

for this distribution, as we shall see, is

that the zones of high relief result from

localised tectonic instabilities, whereas

the areas of low relief are more stable.

The differences between continental

and oceanic areas are due to differences

in the composition, and consequently

the density, of the underlying crust, as

shown in Figure 2.4.

Continental crust

,

with a composition corresponding to

a mixture of granite and basalt, has a

mean density of around 2.8, whereas

oceanic crust

, composed largely of

basalt, has a mean density of around

2.9. Moreover, continental crust has

a mean thickness of about 33 km and

oceanic crust is much thinner, averaging

only about 7 km. This explains their dif-

ference in mean height (or depth) with

respect to sea level. Because the Earth is

in a state of approximate gravitational

balance (termed

isostasy

), the weight of

any particular sector is similar to that of

any other. Consequently, the less dense

continents must attain a higher level

than the denser oceans if they are to

have the same gravitational effect (i.e.

have the same weight). In other words,

we can imagine the continents as being

more 'buoyant' than the oceans, as if

they were icebergs floating on the sea.

Although the mantle underlying the

crust is made up of solid rock (approxi-

mating to

peridotite

in composition),

it is able to flow in the solid state at a

very slow rate of centimetres per year,

enabling it to gradually adjust to the

pressure of gravitational differences

Search WWH ::

Custom Search