Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

may or may not be the places where people live and apply pesticides. The

relationship of residential location and wetlands needs to be considered in

collecting the frogs. The basic principle applies to any type of geostatistical

data collection: all sampling and collection of data needs to take account of

the underlying processes and factors that influence the processes. The com-

plexity of relating sampling and data collection to things and events makes

geostatistics very complex, yet, when properly and reliably done, very reli-

able.

The Ecological Fallacy

A significant mistake easily made when working with geostatics is based on

what is known as the “ecological fallacy.” The

ecological fallacy

is the assump-

tion that the statistical relationship observed at one level of aggregation

holds at a more detailed level. A well-known example of this occurs when

people look at statistics of election results. In most U.S. states in the 2004

election, the majority of voters voted for George W. Bush, but most people

in the cities voted for John Kerry—if you only counted the votes from a city

and assumed it applies for the state, you would be in error. Take another

example: There may be a strong relationship between the number of zebra

mussels in lakes and the number of recreational boaters in a state, but other

local and regional factors in a state may be more significant in explaining the

relationship. The strong statistical significance at the state level may be hid-

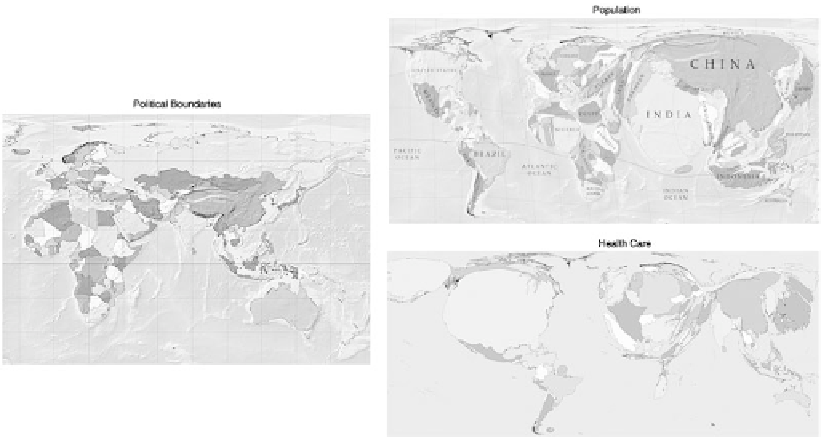

Cartograms show how other geographical characteristics influence mapped attributes, issues that

geostatistics can take into account.

From

www-personal.umich.edu/~mejn/cartograms/

Search WWH ::

Custom Search