Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

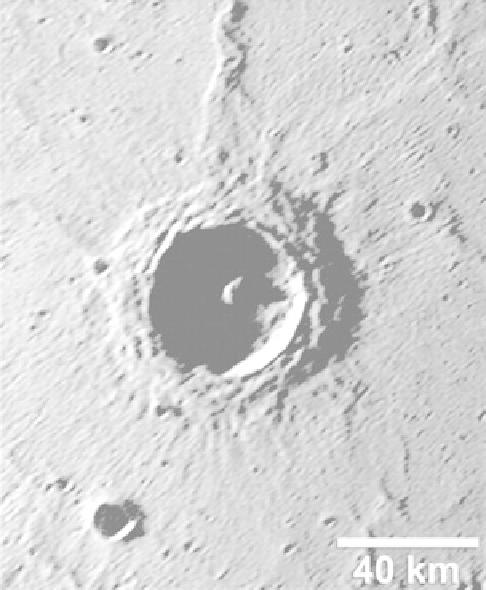

Figure 5.15. This ~95 km in diameter complex crater shows that

the continuous ejecta deposits (outer boundary marked with

arrows) fall within a distance about half the crater diameter

and that some secondary crater chains (asterisk) occur within the

ejecta deposits (NASA MESSENGER images 108826040 and

108826045).

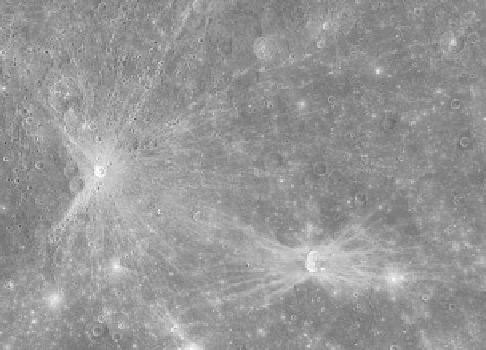

Figure 5.17. The bright-rayed 80 km in diameter crater Debussy in

the southern hemisphere of Mercury (NASA MESSENGER NAC

131773947, NASA PIA 11371).

Figure 5.18. The asymmetric bright-ray pattern around the 15 km in

diameter Qi Baishi crater (left side) suggests a low-angle impact by

an object traveling from west to east (left to right); the

“

butter

y

”

ejecta pattern around the 13 km in diameter Hovnatanian crater

(lower right) also suggests an oblique impact, but it is not known

whether the object was traveling from north to south, or from south

to north (NASA MESSENGER image, NASA PIA 12039).

process involved in the formation and/or preservation of

bright rays in general.

Statistically, most impacts occur at angles that are not

normal (90°) with respect to planetary surfaces. However, as

discussed in

Section 3.4.3

, differences in crater morphology

and ejecta deposits are seen only when the angle of impact is

Figure 5.16. This 44 km in diameter crater is on the

floor of the

Rembrandt basin; the very low Sun-angle illumination emphasizes

the continuous ejecta and its proximity to the rim (NASA

MESSENGER NAC 131766401M).